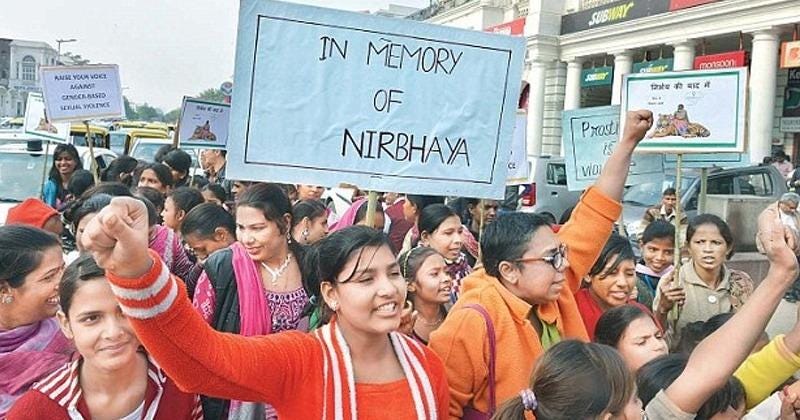

Notorious Delhi Rape Case’s End Means Little for Women’s Safety

Rape is still a grim fact of life in India

By: Neeta Lal

Last week, as India executed six of the four rapists (one was declared a minor; the second allegedly committed suicide) in the unspeakable 2012 Delhi gang rape and murder case of a 23-year-old physiotherapy student, there was collective relief that the law had finally caught up with the perpetrators of the brutal crime.

But while that may …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.