Thailand's Stalled Population Growth: Prescription for Irrelevance

A once-lauded family planning program may have worked too well

Thailand’s economy has been lackluster for years for a mixture of reasons – politics, oligopolies, tourism dependence, past over-reliance on Japanese investment, and weak improvement in agricultural productivity. But imagine just how much worse it would be but for the presence of an estimated 5.2 million foreign nationals.

Few of these are the retirees from the richer world who bring money into the country. Most are low-paid workers from across the borders, mostly from war-ravaged Myanmar with its long border, and some from Cambodia and South Asia. Of these, perhaps a third are “irregular’ – without work permits and thus especially liable to exploitation.

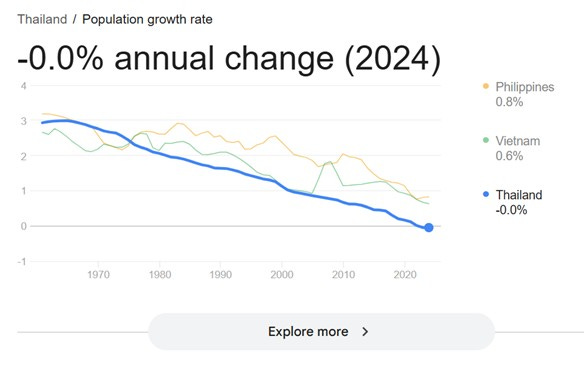

Their presence and increasing number is as much the result of demand as well as supply. The country’s population growth has gone static, partly the result of what has been called one of the most successful USAID programs in history, a 1970s family planning program widely recognized for its effectiveness in significantly reducing the birth rate. Today, Thailand’s TFR, or total fertility rate, has fallen below replacement.

Thailand, where one fifth of the population is over 60 years, is on the threshold of being declared an Aged Society. At 71 million, Thailand’s population is about at its peak, but with more deaths than births for the past several years, the total number is only being sustained by a fall in the death rate. Life expectancy is 77 years and rising. But the overall situation is even worse than in some mature western societies.

For example, the median age of the population is now 40.8 years, the same as the United Kingdom, but Thailand is aging very much faster due to its especially low fertility rate (1.2 births per woman) and lack of official migration. Doubtless if many of those 5 million foreigners were to become nationals and breed, there might be a rise in births as well as in the permanent population.

Thailand’s demographics are a forerunner to what is happening almost throughout Southeast Asia. But as an early starter in (voluntary) family planning programs, and a relatively open attitude to sexual matters, Thailand’s once exemplary achievements back in the 1960s and 1970s when it was still largely a rural economy, leave it facing a situation where, in population terms, it will be a regional minnow by 2050.

Of all the countries in the region, only Indonesia now has a replacement fertility rate – 2.1. Even the Philippines, which long lagged the region in fertility reduction, is down to 1.9, while Malaysia has seen a sharp fall in recent years to just 1.6. (Myanmar data indicates 2.0 but this is not reliable.) Vietnam saw a large fertility fall earlier but may have stabilized around 1.9.

The timing and steepness of Southeast Asia’s fertility declines suggest that by 2050, total populations will be (2024 in brackets):

Indonesia 322 million (285)

Philippines 138 million (116)

Vietnam 115 million (101)

Myanmar 65 million (54)

Thailand 65 million (71)

Malaysia 41 million (35)

On current trends, population growth will eventually stabilize or fall in all these countries but with very different timing scenarios – 2059 in Malaysia and Indonesia but as late as 092 in the Philippines. (Malaysia’s fertility rate is now well below Indonesia’s but earlier was above). Thailand’s population will continue to fall slowly.

There are two lessons to be learned now from this data. The first is that four of five of these countries now know they are headed in the direction of zero population growth and the approximate lengths of time to adjust to both the demands of an aging population and the peaking of the labor force. The speed of the latter is built into the numbers already unless there is sustained rise in normal retirement ages or a sharp change in fertility or death rates.

All this does not just impact health and pension costs, whether they fall on the government or private sector, but on assumptions about needs for increasing numbers of, for example, university buildings and teachers, and the costly public works which were essential to earlier period of population and economic growth but may have become embedded in national budgets. (China provides an example of overbuilding of housing and high-speed railways).

Of course, the situation varies from country to country, and no one would pretend that the Philippines and Indonesia, for example, do not need to focus on infrastructure, physical and social for several years to come.

But Malaysia, for example, may need to focus rather more on its educational standards than its physical infrastructure. The benefits of zero or even negative population growth can only be realized by higher skills and increased productivity. Otherwise, sooner or later, a smaller workforce with static real income has to support a growing elderly population – that is, lower standards for all.

Vietnam is enjoying a demographic sweet spot, but its workforce will peak in about 2039; meanwhile, its enduring preference for male children will militate against official efforts to halt the fall in fertility.

This takes us back to the beginning of the article: the problem of Thailand, which not only faces a numerical workforce decline but an immediate shortage of skills in the digital, robotics, and aerospace sectors, according to a recent report. That cannot be filled with immigration, even if there is some move in by skilled Chinese.

Immigrants currently and for the foreseeable future will be largely of low or unskilled labor. But cheap foreign labor is a crutch and may well, as in western Eutope and the United States, become a sensitive political issue.

Relative to its income level, Thailand has a high standard of public health and access to medical services which will certainly help support the aging population. Thailand also has a long history of small-scale entrepreneurship, and urban-rural links provide a cushion of partial self-sufficiency. Yet, the bottom line is that the nation which once led much of Southeast Asia in economic growth and social change is largely lacking response to its demographic challenge.

Despite a resource base in many ways superior to those of its neighbors, in 25 years it could find itself looking like the sick man of ASEAN, even overtaken by a rebounding Myanmar, assuming the restoration of peace and competent government.

Thailand’s notoriously tight-fisted Finance department, which has kept a grip on politically motivated spending, has ensured that government debt is a relatively modest 55 percent of GDP, or 67 percent if state enterprises are included. Memories of the Asian Crisis still linger so conservatism rules, with a consistently strong external balance and large external reserves. Household debt, however, at about 89 percent, is high for the region, especially considering the demographic situation.

But the sheer lack of any sense of possible crisis down the road may be standing in the way of preparing now for an inevitable future. Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines, take note.