By: Wong Chin Huat

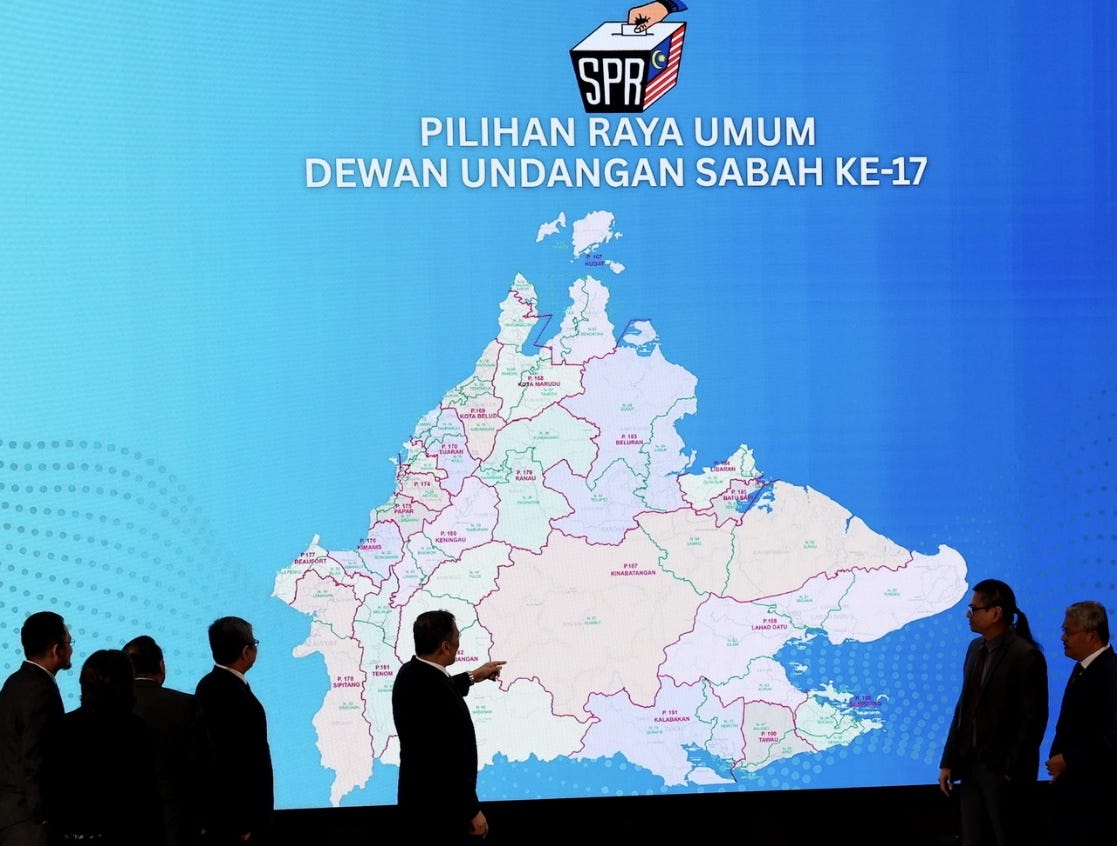

On the surface, Saturday’s polls in the East Malaysian state of Sabah spared Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim his worst outcome – increased independence from the federal government – with his preferred incumbent Hajiji Nor sworn in as chief minister for his second term after midnight, after assembling a 40-seats coalition, exceeding the simple majority of 37. But the wider outcome is unmistakably an electoral earthquake that could shift federal politics, with a near wipeout of national parties. Sabah-based parties and independent candidates received an aggregate 90 percent of the vote vs the national parties, which only received 10.23 percent.

Although the Heritage Party (Warisan), which was demanding increased independence from the national political capital of Putra Jaya, won only 25 of 73 seats, Anwar’s own People’s Parti Keadilan Rakyat won only one of 13 seats contested.

The election has clearly undermined Anwar’s authority as the arbiter between GRS, BN, and PH, the partners in his Madani federal government (as is Warisan), which faces its own problems on the national level. He is expected to deliver a major cabinet reshuffle on Tuesday to seek to deal with declining public approval and a steady stream of corruption scandals, economic problems and other issues. He had tried hard to negotiate an electoral pact to avoid splitting votes to benefit Warisan but only managed to reach deals separately with two GRS and BN to give way to his Pakatan Harapan coalition candidates in most constituencies in which they stood.

This, however, failed to prevent Warisan’s slaughter of Pakatan Harapan allies. The election has clearly undermined Anwar’s authority as the arbiter between the three state parties that are partners in his Madani federal government (as is Warisan). He had tried hard to negotiate an electoral pact to avoid splitting votes to benefit Warisan but only managed to reach deals separately with two to give way to the ruling Pakatan Harapan coalition candidates in most constituencies in which they stood.

Ethnic Chinese flee coalition

Most shockingly, the ethnic Chinese-dominated Democratic Action Party (DAP), the largest component of Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan, which had commanded formidable support among urban Chinese both nationwide and in Sabah since 2008, was completely wiped out by Warisan. Taking the urban seats contested by both DAP and PKR, Warisan is now the face of urban opposition.

Anwar’s ally, the once hegemonic United Malays National Organization (UMNO), took on its two splinters, former Chief Minister Shafie Apdal’s Warisan and Hajiji’s Parti Gagasan Rakyat Sabah (Gagasan) but emerged the weakest among them, winning only five seats, down from 14 in the 2020 election against Warisan’s 25 and Gagasan’s 23.

The decline of the national parties resembles the situation in neighboring Sarawak. There, Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan coalition is the only functioning opposition with only 2 percent of seats in the state legislature and 19 percent of the state’s federal seats. Here in Sabah, the local parties are now consolidated into two blocs, both heirs of UMNO – the Gagasan-led GRS and Warisan.

In Sarawak, the Sarawak Parties Alliance (GPS), the rebranded former Sarawak chapter of the Barisan Nasional, has shrewdly used its one-party dominance to demand concessions from the weakened center, gaining greater control over its petroleum industry and schools. A majority government led by Warisan would be an outright nightmare for Anwar.

To rule out any deal between Warisan and UMNO that might attract minor parties, Hajiji was sworn in at 3 am by Anwar’s powerful ally, Governor Musa Aman, also a sworn enemy of Warisan president Shafie Apdal. Hajiji assembled his majority with the support of PH, United Progressive Kinabalu Organization (UPKO) with three seats, Homeland Solidarity Party (STAR) with two seats, and five independent lawmakers.

With both the Barisan and Pakatan Harapan weakened, Anwar likely faces a more assertive GRS, which may engage in one-upmanship with Warisan in championing Sabah’s demands for more powers and resources from the federal government.

Corruption on all sides

Late last year, Anwar’s influence over GRS was strengthened when a series of secret video recordings showing up to 14 GRS and pro-GRS ministers and lawmakers who admitted to or were implicated in taking bribery for mining prospecting licenses.

As he controls the Attorney General’s Chambers (AGC) and the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), the slow, lukewarm investigation by authorities which resulted in the prosecution of only two lawmakers and the bribegiver-turns-whistleblower is suspected by many as his way of controlling Hajiji.

The whistleblower went nuclear four days before polling, claiming that his secret videotaping operation was approved by Anwar through the Prime Minister’s senior political secretary, who himself took a bribe from the whistleblower. This didn’t rock GRS’ credibility as a local coalition but might have contributed to Pakatan Harapan’s annihilation. It remains unknown if this revelation might cause GRS to be tougher in negotiations over state rights.

The sharp decline of UMNO Sabah, which chooses to stay as a state-level opposition, may weaken the leadership of Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, UMNO president and Anwar’s deputy premier. Zahid has been instrumental in holding UMNO’s 26 federal seats intact for Anwar.

If UMNO experiences any leadership change, some would propose a different alignment pathway for the party: ditching PH and instead working together with its two national splinters, Parti Islam se-Malaysia, and Malaysian United Indigenous Party (Bersatu).

The biggest trouble to Anwar’s balancing act might come through DAP. From top to bottom, the party is fearing that Saturday’s Chinese tsunami in Sabah may threaten its marginal seats and even some strongholds nationwide in the next federal election, which must be called latest by February 2028.

Unlike obligatory voters of UMNO or deferential followers of PAS, predominantly Chinese DAP voters see DAP owing them a huge favor for its surge to power since 2008, not vice versa. They had shown their displeasure against DAP or Anwar with low turnout in some by-elections. In Sabah, they showed the possibility of turning to a rival party.

Some Chinese, which make up 7.3 percent of the population but play an outsize role in the economy, shifted their allegiance from the DAP to Warisan over Sabah’s unfulfilled demands for greater autonomy, or over the GRS state government’s poor performance. Neither would be replicated in the Peninsula.

However, many decided to punish the DAP because they find the party, once vocal as the champion of inclusion and integrity, is now largely muted over political corruption such as the Sabah mining scandal and the attacks on ethnic Chinese by an UMNO firebrand, Akmal Salleh. One hawker in Sabah’s capital city says, “DAP is good in the Opposition, not in the Government.”

DAP leaders have humbly taken in the message from angry voters. They may get tougher next time another corruption scandal or minority witch-hunt happens. In saving itself, DAP may be forced to distance itself from UMNO, once its sworn enemy.

Anwar’s task as the arbiter between UMNO-DAP would be tougher than his failed role in GRS-BN.

Wong Chin Huat is a political science professor at Sunway University, Malaysia

This is more than a seismic shift. More than an earthquake. It is not a kiss on the cheeks Anwar Ibrahim would have been expecting. It was a slap to his face. A spit. Bullseye. And much deserved. Anwar has lost all credibility. He hangs to his political legitimacy by the skin of his teeth. In the next two years, I expect it will completely evaporate and he and his Madani brethren, will be swept away. After the Sabah polls, Madani is in tatters -- again, deservedly. Anwar and his servile Madani maladroit followers, having tethered themselves to his sarong and songkok, have played footloose and fancy free for far too long. At the forefront of the Madani regime has not been clever, even remotely intelligent policymaking, but public relations and Goebbels-like propagandizing led by Fahmi, Mahathir's attack dog, not dissimilar to any of UMNO's previous lineup of pathetic attack dogs. The Madani regime is in fact the UMNO of old and a loosely-cobbled Barisan Nasional dotted with personnel who are more than thick as thieves but are thieves. Now there are thieves within the Madani regime that reach up to the prime minister's office and his inner sanctum.

Looking as Sabah election results alone is reasonable but myopic, especially since Anwar's third leg Hajiji is shackled to the chief minister's post. But Hajiji's reign is tenuous, at best. Apdal of Warisan will be snapping at his ankles the whole way. The way to rid Hajiji is to ride Anwar's other 'yes man' Musa Aman. He has been too politically pliant to Putrajaya -- a renowned Anwar crony and despot of near-zero principles. But so is Anwar, who has fundamentally lies his his support base over long-promised reforms, which he has conveniently ditched and has tried to centralize political power in his hands, just as his previous mentor Mahathir Mohamad had done. That power centralization looks doomed.

Anwar has been on larger chunks of Malay and almost all of the non-Malays' noses from the start. His history of broken promises, blatant lies and bald-faced conspiracy theories are legendary ever since he was imprisoned by Mahathir. He has become so politically and personally desperate to hang on to power that he -- probably -- mastermined with Zam Baki, head of the anticorruption agency MACC, to arrest Albert Tei, the businessman who bribed Sabaha politicians and turned whistleblower out of frustration for not being cheated by untrustworthy, corrupt Sabah politicians, in an episode that reenacted Anwar's arrest in 1998 by cowards -- men without testicles -- from the police and MACC, to silence Tei from further exposing Sabah-Federal shenanigans days before the Sabah polls. It's too glaringly convenient. Noen of the arrest would have come without Anwar's dirty hands in the plot. Just shows just how much more balls-less Anwar has become.

Meanwhile, ina country internationally renowned for its state-nurtured filthy racism and corruption pandemic, it might mean business-as-usual -- for a while. As long as Azam Baki, whose own morality and ethics are highly questionable, is kept in his role by Anwar's personal sanction, the Malay-Islam led filth of racism and corruption, and the dirtiness of patronage politics will remain -- until early 2028. By then more of the Anwar-Madani rot will be exposed. If the DAP, a Chinese party in the Madan coalition, has even an ounce of principle left in its dried-up bones, instead of playing second-fiddle to Anwar's disgusting politics of old, and leaves the regime to save what little respect is left of itself, I expect the DAP to be crushed in 2018 -- deservedly. From the complete idiocy and nonsensical horseshit that Lim Kit Siang & Co used to mouth off about creating a "Malaysian Malaysia," and Anwar's dogshit about a "New Malaysia", really this is old Malaysia, the real Malaysia, not "truly Asian" (that other claptrap that is spread like venereal disease, Malaysia has turned backwards politically and ideologically, most of it because of the backwardness and ugliness of religion politics. That said, its economy continues to be built on sand, which is part of the same old political story, in so many ways.

The diversity and grand passions of a much larger country, but with the pettiness and vendettas of a smaller one. The worst of each.