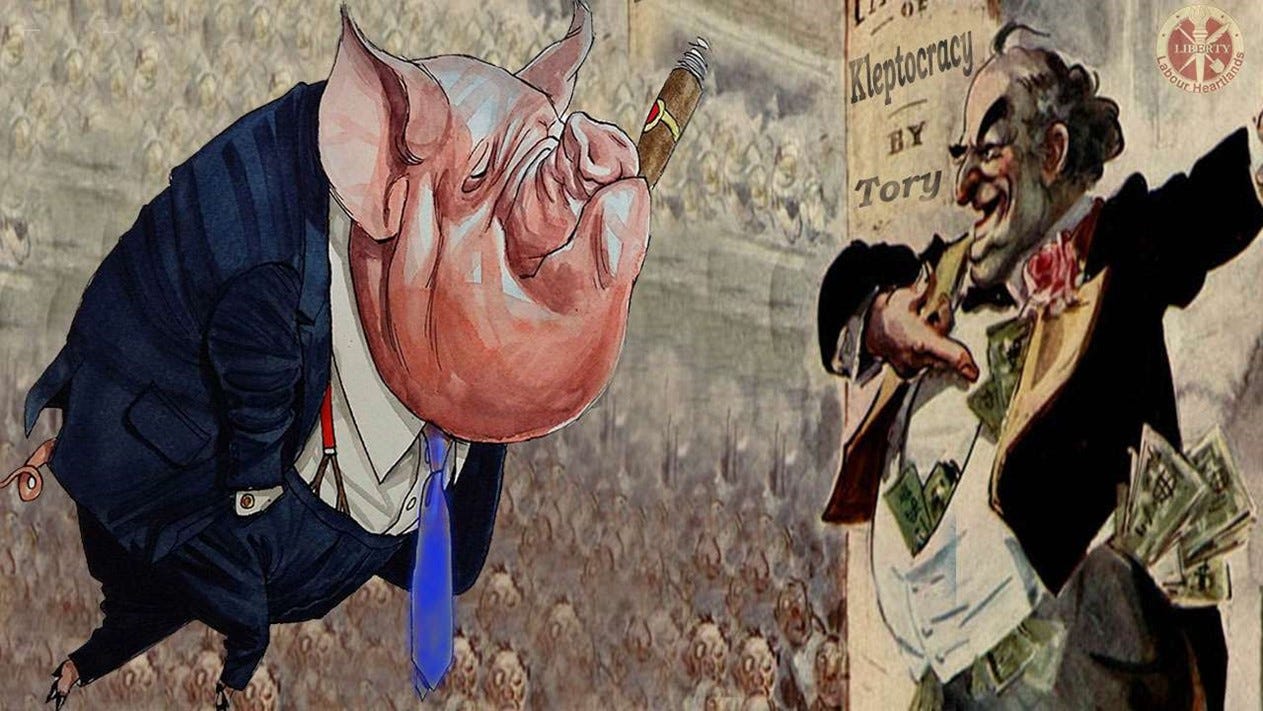

The Rise of the Kleptocrat

Transparency International’s co-founder issues a call to stiffen laws

By: Frank Vogl

It is a fact today that almost all authoritarian regimes are run by kleptocrats who steal from their citizens while ruthlessly abusing their human rights. The crimes being perpetrated by the governments of Myanmar, Malaysia, Iran, Egypt, Nigeria, and many more nations, not only impoverish their own citizens. They ultimately impoverish all …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.