After years of living and studying in Iran and growing accustomed to different social norms, hundreds of thousands of Afghan women are now compelled to return to Taliban-run Afghanistan, a return that is not simply a geographic relocation but a profound rupture of culture and identity. They are not just displaced people nor mere entries in a statistical column. Each returning woman is a small history of learning and loss, of hope and fear.

For decades, Iran’s shared linguistic and cultural ties made it a second home for millions of Afghan migrants. Women in Iran have faced systematic state pressure for years—compulsory dress enforcement, gendered limits in public culture including music and performance and other restrictions beyond the home.

Western portrayals of Iranian women are often cast in stark tones of religious and social oppression; the reality is more layered. Iranian women stand on a deep civilizational bedrock more than 2,500 years old, carried by centuries of literature and philosophy, visual arts and architecture, and an urban habit of debate that has been both constraint and capital. Out of this tension, durable roots of resilience have grown.

Violence and discrimination against women are global; no geography is immune. Inside Iran, in many local settings—under the weight of customary codes, religious readings, and communal rules—women still carry heavier burdens. Yet over recent decades, they have refused to relinquish claims to dignity and rights; pushed back, regrouped, and returned more informed and determined.

The symbolic crest of this continuum was the nationwide 2022 protests under the banner Woman, Life, Freedom—a moment that reminded the world that behind numbers and news sits a living will for change. Institutionally, gaps with parts of Europe and the United States remain, but in human talent, literacy, creativity, and social resolve, Iranian women are not lacking. And by regional comparison, in several indicators and arenas, they are often ahead—even if the path has been uneven. Iran may trail the West on women’s rights, yet it remains markedly more open than Taliban‑run Afghanistan and, on some measures, parts of South Asia.

That is the empirical context many Afghan women have experienced while living in Iran and it is the reason their expectations upon return diverge so sharply from current realities in Afghanistan. These refugee women, shaped by Iran's complex socio-cultural milieu, including its history of women's activism and evolving public sphere, now face reintegration into Afghanistan's more rigid traditional frameworks, a context marked by what many observers call gender apartheid.

The Demographics of Forced Return

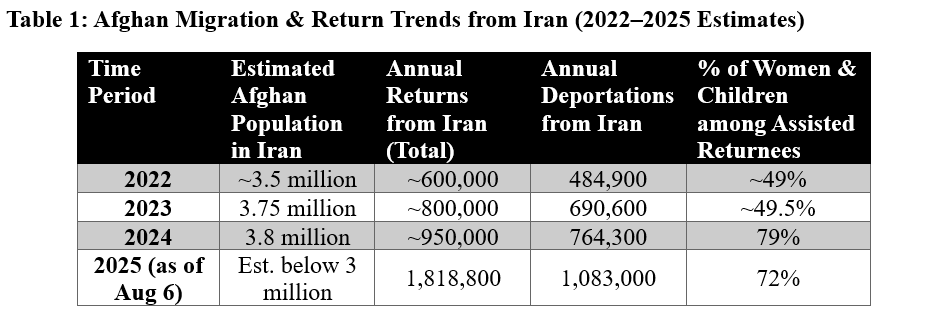

While a fully harmonized 10-year time series is not publicly available, recent figures from the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) show an alarming surge in returns, especially from Iran. From the start of 2025 to August 6, more than 2.1 million Afghans have returned from Iran and Pakistan. Iran’s share is striking: about 1.82 million returned from Iran, of whom about 1.08 million (60 percent) were deportations. This represents a dramatic escalation from previous years.

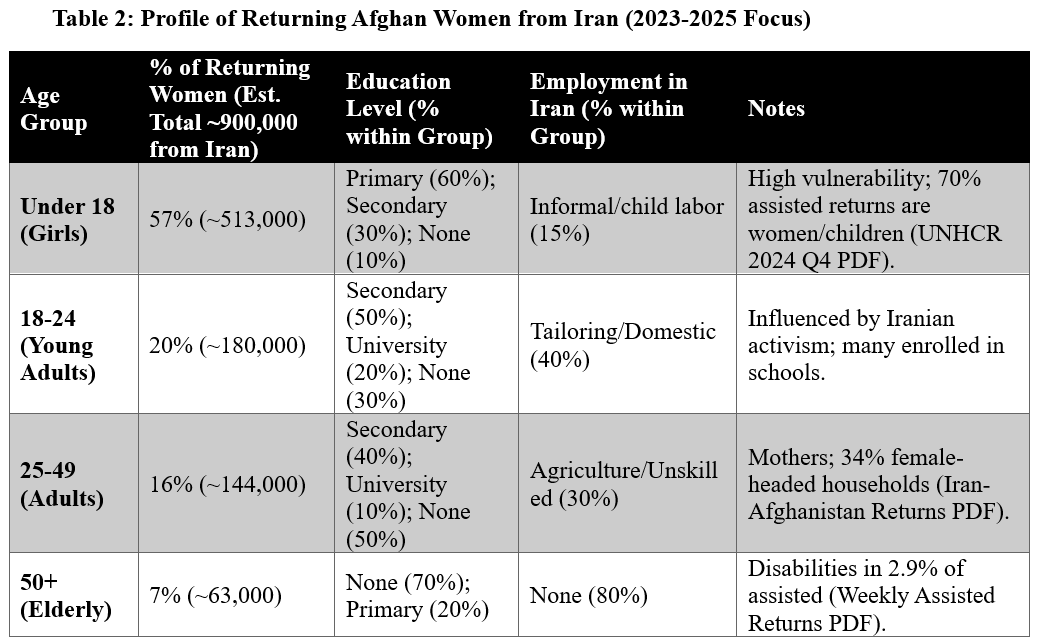

The data reveal a rapid, forced return in which women and children predominate among assisted groups. Roughly one-third of household heads report some formal schooling—often gained in Iran. This cohort, numbering hundreds of thousands of women from Iran alone since 2023, carries a different societal outlook into an environment largely at odds with that learning.

Worlds in Contrast

Iran and Afghanistan share linguistic and historical ties, yet their socio-cultural landscapes for women diverge markedly. This comparison, drawing on scholarly works such as Valentine Moghadam’s Modernizing Women, highlights these differences without implying hierarchy.

Iranian women, despite post‑1979 Islamization, have a decades‑long record of reclaiming public space through universities, professional associations, independent media, and neighborhood organizing, culminating most visibly in the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom mobilizations. This repertoire includes legal campaigns around family law, workplace equity efforts, and digital activism that broadened civic skills for a generation.

By contrast, in Afghanistan, limited pre‑2021 gains – urban schooling, women in broadcasting, NGO leadership – have been rapidly rolled back under the Taliban through a cascade of edicts: bans on girls’ secondary and higher education, restrictions on NGO and public‑sector work, compulsory mahram requirements for movement, and the shuttering of parks, gyms, and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs. The effect is a near‑total contraction of women’s public sphere and the criminalization of everyday participation.

Religious and Cultural Norms

While both are patriarchal societies, Iran's urban contexts offer more space for negotiation. Child marriage, affecting 28 percent of Afghan girls versus a still-disturbing 17 percent in Iran, and polygyny, a norm in rural Afghanistan but largely stigmatized in urban Iran, reflect these deep divergences.

Afghan women returning from Iran, where they had access to universities and relative freedom of movement, confront a reality of tighter dress and mobility codes, guardianship rules that condition access to services, and community expectations that relocate decision‑making from the individual to male kin. Everyday choices – schooling, health visits, paid work, even phone use – are reinterpreted through stricter religious and customary frames of purdah (seclusion) and state-enforced dependency.

The return of this cohort produces two simultaneous, even contradictory, effects.

Accustomed to Iran’s relative freedoms, they confront Afghanistan’s severe constraints. This induces anxiety, depression, and identity crises, exacerbated by forced family separations (35 percent of returnees request family reunification support). Psychologically, forced returns amplify trauma, with elevated PTSD rates reported among returnees.

UNHCR monitoring shows that primary needs upon arrival are food (88 percent), shelter (81 percent), and financial assistance (79 percent) – a survival posture that worsens mental health vulnerability.

These returning women, predominantly a young cohort, with women and children forming the majority of those assisted, could catalyze gradual change. As mothers, they could foster progressive norms and resist harmful traditions like child marriage within their households. However, their small number relative to Afghanistan's total population and their lack of social or economic power under the Taliban may limit their impact.

With around half of returning household heads reporting no marketable skills, their ability to act as independent agents of change is severely constrained. They risk becoming marginalized “regional anomalies” rather than drivers of national transformation.

Echoes of Exile in a Quiet Emergency

What unfolds along Iran’s eastern frontier is more than a migration policy story. It is a gendered humanitarian crisis. We are witnessing the compelled return of a generation of women suspended between two worlds. In Iran, they learned the grammar of agency –how to ask for rights not as slogans but as everyday practice. Now they are sent back to a polity that walls off the very spaces where those practices live.

These women represent human capital that might have helped shape a different Afghan future; now they themselves face acute psychosocial risk. This analysis does not prescribe a grand solution, as those levers sit with policymakers who rarely hear these women’s voices. Its aim is to carry their silent cry into public view.

In sum, the forced return of Afghan women from Iran is an under-examined socio-economic crisis producing a generation caught between two worlds, with deep ramifications for mental health and Afghanistan’s social fabric. Their names are not numbers. Their return is not a spreadsheet. It is a profound social unraveling—and a test of our capacity, as a region and as a world, to keep small doors open for learning, dignity, and hope.

Each returning woman is a small history of learning and loss, of hope and fear....

What a painful sentence!

Each returning woman is a small history of learning and loss, of hope and fear....

What a painful sentence!