By: Manuel L. Quezon III

On May 12, Filipinos conducted an exercise they’ve regularly done since 1938: they held a midterm referendum on the sitting president. The result, pass or fail, wouldn’t be decided in the House of Representatives or the many local positions from governor to councilor also up for grabs, but rather, in one arena only: the Philippine senate, where half of its membership was up for election, too.

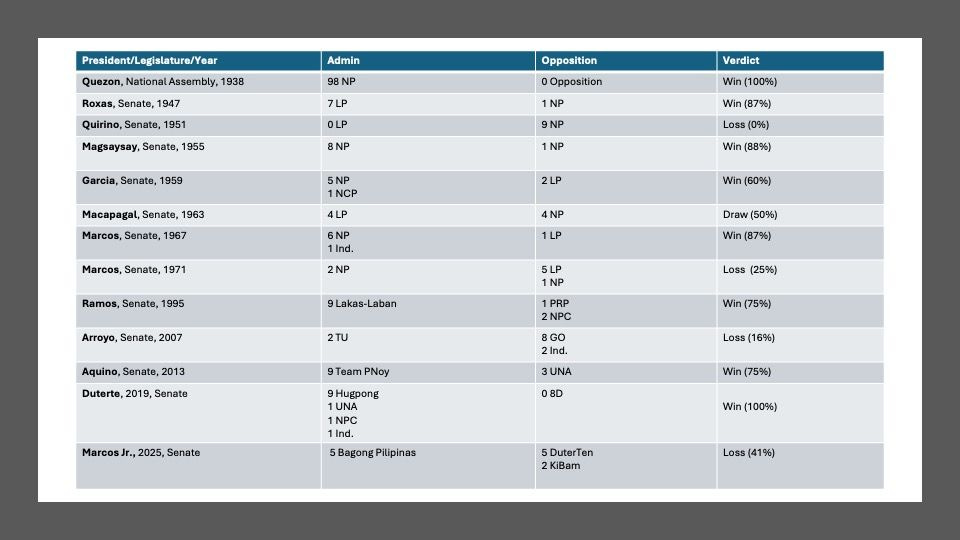

The senatorial results traditionally serve as the bellwether of lame duck status. Prior to 2025, three presidents had suffered a midterm repudiation: it foreshadowed doom for two of them (Elpidio Quirino in 1951 who lost reelection in 1953, and Ferdinand E. Marcos in 1971, who then proclaimed martial law less than a year later), back in the days the presidents could still run for reelection. For Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who suffered the second-biggest midterm defeat in 2007, it augured trouble to come and the impossibility of engineering a favorable succession.

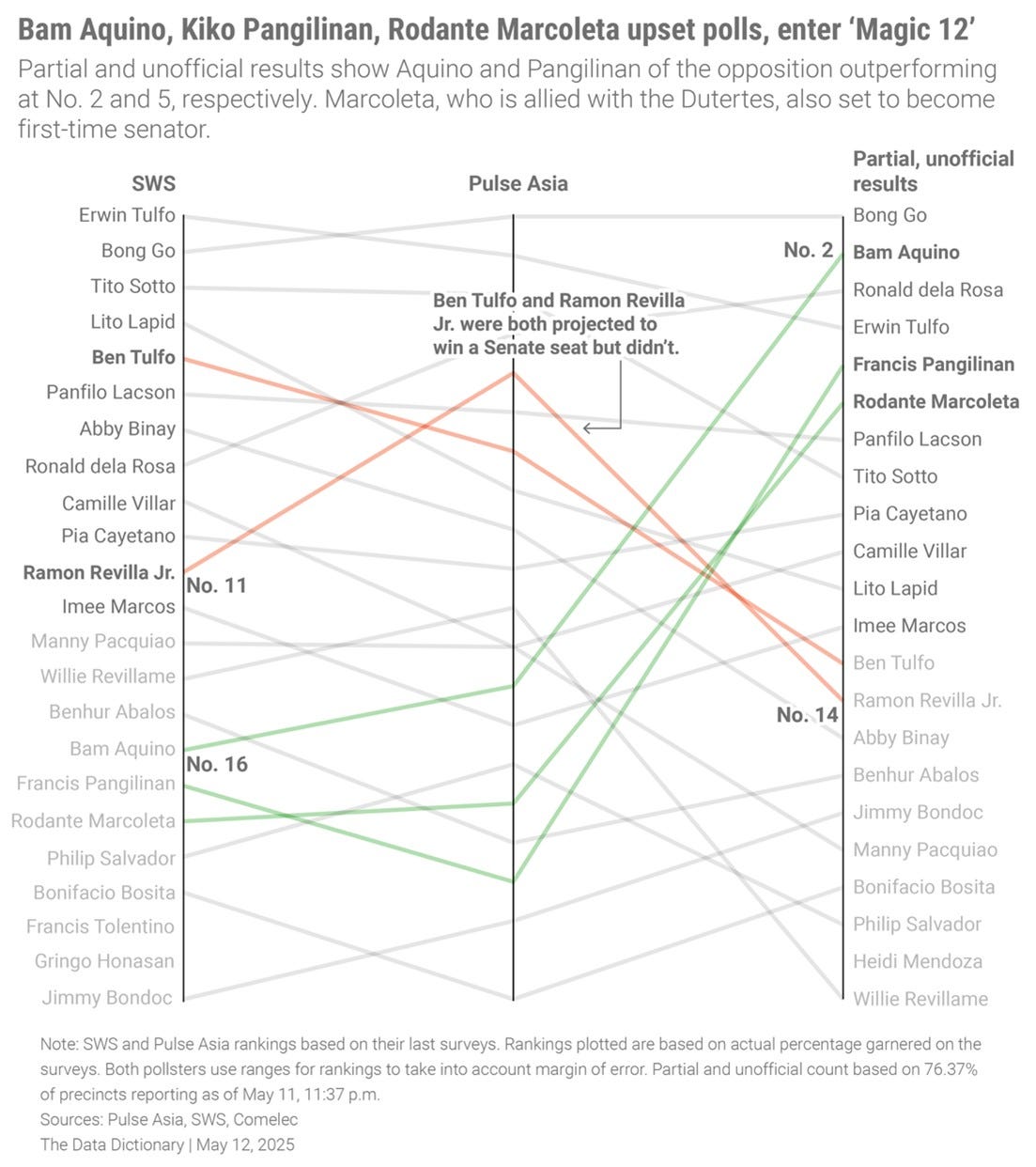

Turnout was exceedingly high for a midterm, approximating that of a presidential election. The polls closed at around 7 pm and from 10 pm to midnight, the writing was on the wall and it was a shocker. In the first place, the four reputable survey firms had essentially failed to accurately predict the results. No one had expected the administration to do well, but it did worse than expected. The verdict was five senators from Marcos’ coalition, five for the Duterte coalition. The biggest surprise of all was that two from the ranks of the centrist coalition that both Marcos and Duterte had crushed in 2016 and 2022 – Bam Aquino (of the famous clan that loyalists of both the President and Vice President had waged vendetta against) and Francis Pangilinan, defeated vice-presidential candidate in 2022 – would be returning to the Senate.

For the public keeping score, the verdict was clear: Marcos 5, everybody else, 7. A defeat.

But the main battlelines betray an important detail: it was also a tie. The main camps, after all, ended up in a draw, with five senators each. This, despite the clearly existential stakes for both the President and the Vice-President. It’s no surprise then, that Marcos’s philosophical election statement was exceeded in its lack of enthusiasm, by the Vice-President’s, who more frankly expressed disappointment.

The political reality is that the battle was joined between two sides with nearly unprecedented advantages that both squandered.

Marcos had the advantage of incumbency, and of momentum, with his first cousin, the Speaker of the House, having impeached the Vice-President and his secretaries of justice and the interior managing the apprehension and handover of former president Duterte to the custody of the International Criminal Court where he is standing trial.

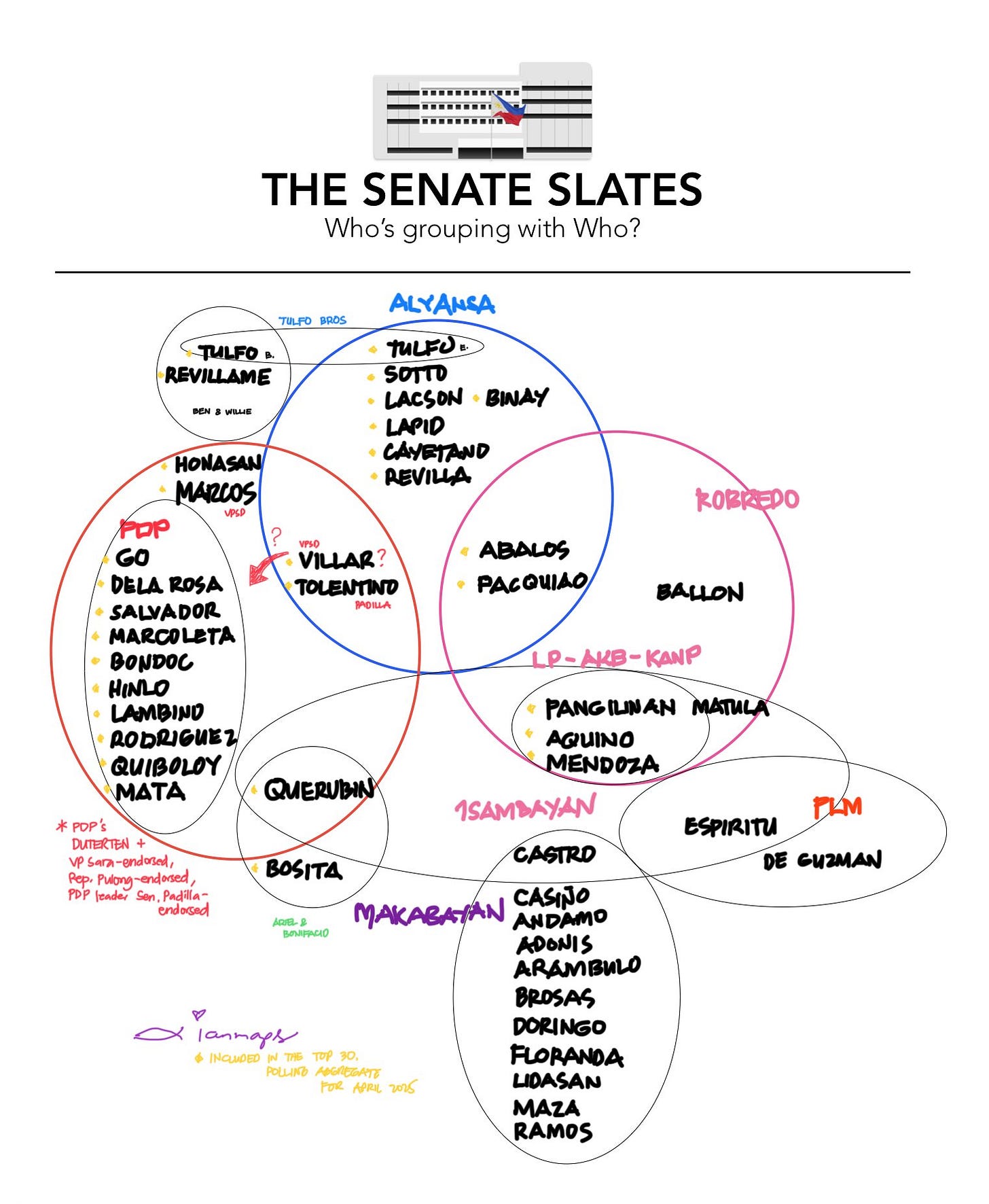

Marcos had no shortage of resources; he alone had been able to cobble together a full 12-candidate slate, and it was a highly conventional one, a combination of increasingly long-in-the-tooth but electable veterans, relative newcomers considered personally valuable to the presidency, or legacy candidates preparing to take their turn at the trough.

What Marcos lacked was popularity. He was the first post-1986 president to achieve an electoral majority, but by the time the midterms approached, public opinion had soured, with nearly three of four voters unhappy with his administration. While big business was happy with him, the public wasn’t when it came to inflation. While Rodrigo Duterte himself had started the rift that eventually erupted into open hostilities, his daughter was able to frame it as a case of a hapless Marcos unable to rein in the appetites of his wife and his first cousin, the speaker. And what Marcos failed to keep together –his winning coalition—he further proved incapable of maintaining cohesion on his side of the fence. By election day, two of the President’s candidates including his elder sister, Senator Imee Marcos, and Camille Villar, the daughter of a former Speaker of the House (and one of the country’s richest plutocrats) had left his camp, seeking the endorsement of the Vice-President Sara Duterte and her father.

The 10-candidate rump of the President’s slate proceeded to mount an unimaginative campaign, with its leading vote-getters gradually sinking. Half proved viable, in the end, not least because of the corresponding weakness of the Duterte slate.

Duterte slates, to be precise, because until the very end, there were two power centers in the Duterte Universe: the former President himself and, in his absence, his common-law wife, Honeylet Avanceña, and the Vice-President herself. They didn’t necessarily see eye to eye on who deserved to be considered part of the Elect. The most bankable of the Duterte acolytes, his political Man Friday, Bong Go, for example, was always considered close to Honeylet but despised by Sara; and when Imee Marcos, seeing her poll numbers plummeting, gambled on disowning her brother, Sara anointed her while Honeylet refused to do so. The Dutertes, in the end, could only mount a slate of 10, with only incumbent Senators Go and Dela Rosa, old-time henchmen of the former president both, as their star attractions; the rest were either obscure and unelectable, or disgraced and the same, like Pastor Apollo Quiboloy campaigning from jail. Neither slate had a chance to sweep the field.

The lackluster nature of both slates goes a long way to explaining the electoral surprise that ensued. Here, a few pieces of conventional wisdom are relevant. The first is that Filipinos hardly ever vote straight tickets; they mix and match senatorial candidates. The second is that time and again the tendency of the average voter is to have eight top-of-mind candidates and either leave the remaining four slots unfilled, or liable to being filled out on the basis of a whim, or an appeal, or more mercenary reasons. The third is that while national parties are essentially decorative, local political machines have remained durable and have an estimated effect on the outcome amounting to as high as 5 percent of the votes cast.

With the two main slates either lackluster or saddled by a combination of inept coalition-building or being tied to an unpopular incumbent, and both slates, furthermore, being incomplete, even the loyal from either side had no incentive to vote for 12 senators. The average voter mixing and matching would have had a limited pool from which to choose. Even command votes would have been hard-pressed to vote for 12.

In the midterm of 2019, the 12th placed senator received 30 percent of the vote; in 2025, it seems 23 percent was enough to secure last place. One of the surprise winners, Bam Aquino, with the vote he obtained in 2025, would only have earned the 7th slot in 2019 though he came in second this time around. And yet, with voter turnout at 81 percent – presidential election levels—it suggests many voters didn’t bother to vote for 12, which in turn explains the surprising results for Aquino and Pangilinan, neither of whom were predicted to make it by the reputable surveys.

With both Marcos and Duterte slates at 10 slots each, and with Marcos wanting to keep two turncoats –the President’s sister and the former Speaker’s daughter—out, it wouldn’t be unimaginable for the two oppositionists to be preferrable to both sides as at least opposed to their main opponent, too. Put another way, both having waged campaigns “above the fray” in not actively antagonizing either Marcos or Duterte, focusing on their own initiatives of education and food, respectively, they could easily become the lesser evils for both machine politicians and the general public. This goes a long way to explain the unique set of circumstances that pole vaulted them into the winning circle.

Hence, the contest being a tie that resulted in a defeat: a validation of the thinking that led then-Vice-President Leni Robredo to challenge Ferdinand Marcos Jr. for the presidency in 2022 and the union of Marcos and Duterte, temporarily though it was, to present an unbeatable combination. If the Marcoses and Dutertes hadn’t combined, they might have canceled each other out, and Robredo could have won the presidency. As it stands, Marcos and Duterte canceled each other out, giving a second wind to cohesive, but downcast, coalition that didn’t expect to win, but did (it’s a sign of true weakness, though, is that it had the smallest senate slate of all).

What made this year’s midterm such good copy is that it is a proxy fight as much as it is a plebiscite. Since Vice President Duterte’s been impeached, the first order of business of the new senate, with half its membership decided in this election, will be her trial. Sixteen votes are needed to convict; with the results as they stand, acquittal has six firm votes. The remaining 18 senators are nominally uncommitted though most observers believe it will be an uphill climb for conviction. The House, however, remains firmly in the administration's hands, most, though not all, of the congressmen and women who’d impeached Duterte have survived the midterms. Public opinion, in the end, based on the conduct of the trial, will have an outsized effect on the outcome.

Manuel L. Quezon III is a Filipino writer, former television host, and a grandson of former Philippine president Manuel L. Quezon

Such convoluted writing. Took me three goes at reading this story or analysis to understand the writer's central point or argument. Seems to me there's a challenge amongst Asia Sentinel contributors of who can jam a dozen contending ideas into the first paragraph that is also a single sentence, even if it is paused with a comma or a semicolon, and then hope for the best.

Essentially the result of the elections is a three-way tie. There are no real winners. Not effective ones at any rate. All three are as useless as they come. But there are losers. The losers are the people of the Philippines. They are leaderless, just as throughout Philippines history the Filipino ship is rudderless on choppy waters. The people are deeply divided. But how can you tell when voting is along the lines of tribal loyalties? It's feudalistic even for a country of so-called Catholics. Yet, as the late Christopher Hitchens has written, "god is not great". In the Philippines, we know why. Apparently the people do not. How do you vote for a criminally-deranged Rodrigo Duterte who has the blood of more than 10,000 Filipinos on his hands, and by extension for his daughter his daughter, who so mindlessly supported her father's lust for spilling Filipinos blood through vigilante mass murder via his Mindanao-imported thugs?

I agree with the writer that Marcos Jr had the advantage and though he won the election -- by the skin of his teeth -- effectively he also lost it because of his incompetence. So, in the Philippines case -- unlike Australia's and Canada's in their recent elections, incumbency mean bugger all in the Philippines. But to be fair, how does anybody expect Marcos Jr to run a regime that has a spoiler like Sara Duterte as his vice-president who's constantly out to cut his throat any how she can? Meanwhile he people suffer, especially those who are historically entrenched in structural poverty. Never mind the Philippines' high GDP growth rate: it's obvious economic development in that country remains highly skewed to favor the filthy-rich classes, most of whom are rent-seekers or capitalist parasites. This isn't going to change any time soon. In fact, given the election results, the socio-economic life of Filipinos from the low middle class down is only going to stay the same or worsen. Seems to me religious virtue of being truthful in the Philippines, amongst its greed and power hungry political class, and of their capitalist cronies, is nothing more than a grand hypocrisy and lie.

So let the grand old Philippines' political games not begin but continue. How many more Filipinos will leave the country to sell their labor to foreign capitalists on the dirt-cheap, to be exploited to the hilt, to be abused and discarded, because the Philippines state refuses to look after its own people for its dirty, nasty, bloodyminded, corrupt politics?