Patients betrayed: Malaysian Medical Council Protects its Own

Regulatory agency goes with the malpractice flow

By: Murray Hunter

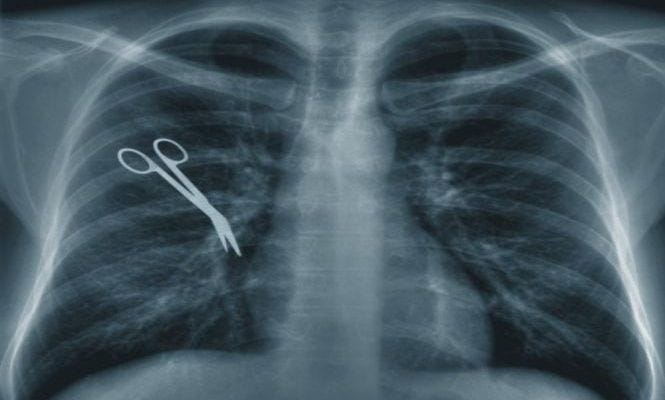

Concerns are growing in Malaysia that trust in its healthcare system is struggling under the weight of declining standards, rising incidents of malpractice and failure to hold errant doctors to account, an existential threat to the country’s ambition to market itself as a Southeast Asian medical tourism destination.

Mohd Ismail Merican, …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.