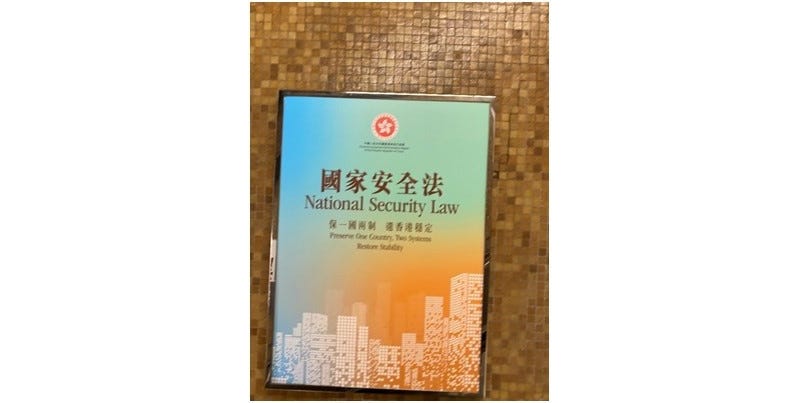

National Security Law Descends on Hong Kong

New details already generating fear

On June 21, some people in Hong Kong watched a partial eclipse of the sun. Now they fear the final eclipse of Hong Kong’s autonomy via the national security law passed by the National People’s Congress in May. Details of the law have been made, with likely implementation on June 30 — just before the anniversary of Hong Kong’s July 1 return to China, in …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.