By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

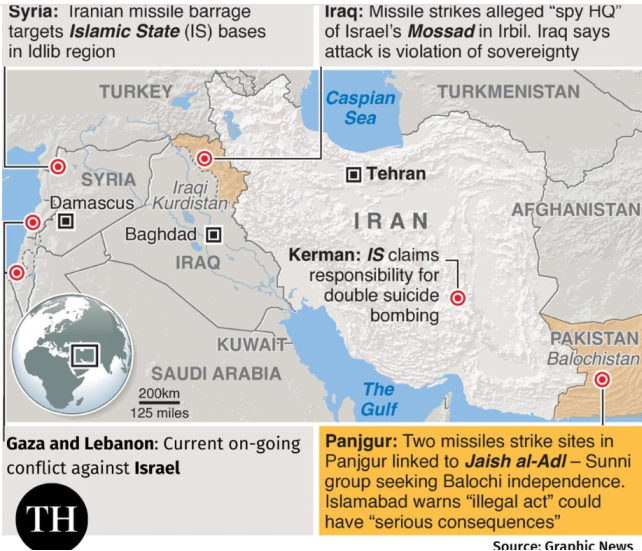

With Iran and Pakistan exchanging military strikes earlier this week, tensions in the wider Middle East stand to rise. Iran launched missile and drone attacks that reportedly targeted hideouts of anti-Iran Jaish al-Adl based inside the Pakistani part of Balochistan. Women and children were killed, with Islamabad retaliating with its own strikes into Iran, aimed at Balochistan rebels hiding over the border.

For many, Iran’s attack, while not unprecedented, and Pakistan’s retaliation, which is, might be a prologue to the spread of the Israel-Gaza conflict. But as with Iran, domestic, rather than international, imperatives are at play. Neither Iran nor Pakistan targeted each other’s military bases. There is reason to believe that no war will erupt. These strikes are much more political than strategic, serving few security purposes.

Pakistan, facing a debilitating financial crisis, an incipient rebellion in the restive Balochistan province, and a growing problem with its onetime client state Afghanistan, has no appetite for a face-off with the Revolutionary Guards. The Iranian regime is under pressure due to the war that began with Hamas’ attacks on Israel on October 7.

The start of the Gaza conflict was immediately followed by reports that claimed Iran’s support for Hamas to sabotage the now-moribund Abraham Accords to prevent wider Arab-Israel normalization to avoid its permanent isolation in the region and beyond.

Beyond providing support, logistical and otherwise, to Hamas, the Israel-Gaza war has cost Iran in other ways. Its ally in Lebanon, Hezbollah, has been attacked several times by Israeli forces. A top Iranian military “adviser” was killed in Syria in another Israeli strike. When the twin bombings on the death anniversary of Qasim Sulemani, the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards killed in a US strike in January 2020 in Iraq, killed at least 84 people in Iran in the first week of January, it not only came as a surprise to Tehran but also put a question mark on the regime’s ability to protect its people and resist Israel.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s aging leader, promised a “harsh response,” which has materialized in the form of separate Iranian strikes in Iraq, Syria, and Pakistan. In Iraq’s Kurdistan region, Tehran claimed to have targeted and successfully destroyed an Israeli spy hub near the US consulate in Erbil, the Kurdistan regional capital city. In northern Syria, Tehran targeted the Islamic State, which had accepted the responsibility for the twin attacks.

These strikes have allowed the Iranian regime to demonstrate, both to domestic and international audiences, its ability to hit targets outside of its borders. The fact that Tehran didn’t hesitate to strike Pakistan, a nuclear state with a powerful military force, sent a message.

The publicity given to these strikes is also new. In 2014, when Iran fired rockets into Pakistan, the incident didn’t become a major diplomatic issue, nor did Tehran proclaim it – or publicize it via media – as a step taken to protect its security. But the recent strikes have been given a lot of publicity, with top officials framing them as their response to those seeking to destroy Iran.

This messaging is both a response to the earlier attacks on Iran and an outcome of the fact that the power of hardliners in Iran is increasing, a development that can be traced back to the anti-hijab demonstrations that erupted in September 2022. In Iran, such protests are almost always seen as an anti-regime conspiracy. In line with that, the fact that the Revolutionary Guards have themselves come under attack also implies an anti-regime conspiracy primarily because the core purpose of the Guards’ existence is to protect the regime (rather than the country itself). Therefore, when Iran was attacked internally and externally, it became absolutely crucial for the Guards to take any and all necessary steps to demonstrate their preparedness to protect the regime.

Pakistan’s Retaliation

Pakistan reportedly targeted the Iranian hideout of the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF), a Baloch militant group fighting for the independence of Balochistan from Pakistan. While Iran confirmed that nine people, all of them “foreign nationals,” were killed, the BLF denied that it has any hideouts in Iran and/or any of its fighters were killed. But what the BLF says doesn’t matter much.

When Iran struck Pakistan deep inside its territory and Pakistan failed to intercept incoming Iranian missiles and drones, questions began to be asked – especially on social media, about the capacity of the Pakistani military forces to defend the country against any surprise attacks.

These questions came as a blow to Pakistan’s military establishment, which was accused of spending more time managing Pakistan’s politics and the upcoming elections than defending the border. Pakistan’s initial response to recall its ambassador didn’t automatically take out the fire, forcing Islamabad to execute a tit-for-tat strike.

What made this strike even more crucial is the ongoing anti-military Baloch protest movement. For more than month, Baloch activists led by a woman, Mahrang Baloch, have been protesting in Islamabad against enforced disappearances and extra-judicial killings of Baloch activists. These protests directly accuse the military of forcibly disappearing and killing Baloch people.

The Pakistani military, on the other hand, frames the entire Baloch movement as a foreign-funded conspiracy aimed at disintegrating Pakistan. The fact that Pakistan claimed to have taken out a BLF hideout inside Iran is meant to give credence to Pakistan’s narrative of Baloch nationalism being a foreign-funded movement and that Pakistan’s security forces, which claim to be the defenders of Pakistan’s territorial and ideological frontiers, are ever ready to take all necessary measures to ensure this defense.

More generally, it helps the military establishment to dispel the impression that it is involved in politics and not doing enough to defend the borders. Such framing allows the military establishment to dodge other key foreign policy questions. For decades, the military has dominated Pakistan’s foreign policy. As it stands today, Pakistan’s relations with three neighbors – Iran, Afghanistan, and India – are worse. Could there be a better indication of a flawed foreign policy than this?

But the military’s massive framing, accomplished via social and digital media, of its ability to strike back leaves minimum to no space for these questions to be raised and/or debated. Like the Revolutionary Guards in Iran, the Pakistani military directly benefits from such clashes, with all of this collectively nullifying any possibility of a direct war between both countries.