Iran's Inflation: Rooted in Institutional Failure

Pervasive nationalization, state intervention and the eclipse of the private sector

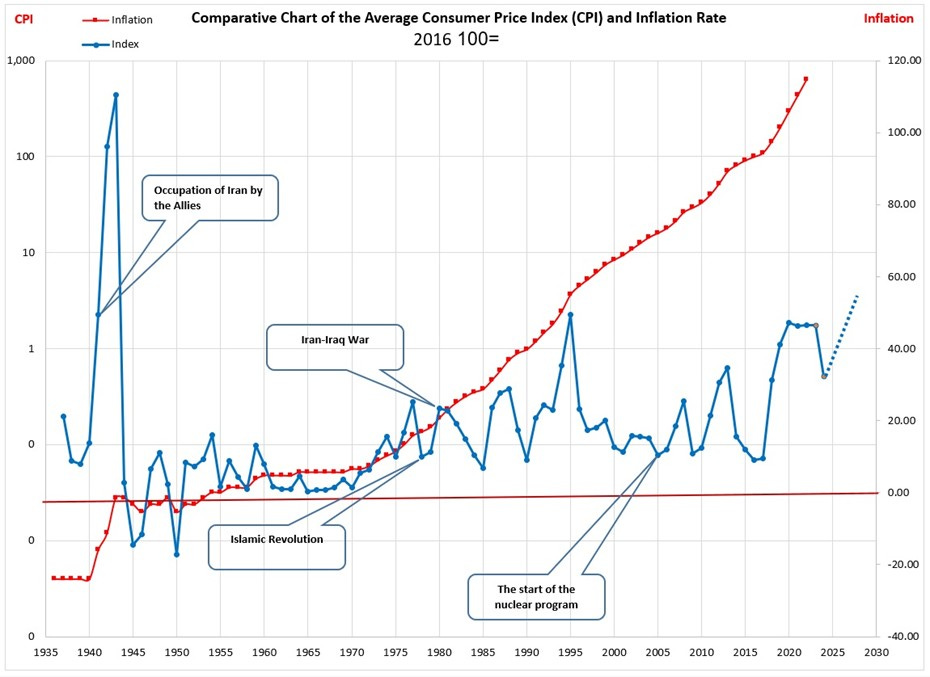

Iran’s economy over the past five decades has been gripped by persistent, complex inflation, rooted in deep structural failings, the preeminence of security and nuclear imperatives, and the systematic corrosion of institutional legitimacy and social capital that has damaged families by eroding their purchasing power and increasing poverty levels, leading to hardship in affording basic necessities and even impacting essential services like education and playing a major role in the migration of thousands of the country’s best-educated citizens.

Contrary to accounts that attribute inflation merely to price shocks or monetary laxity, problems stem from the architecture of its political economy, the geopolitical strategy of its rulers, and the clash between the intentions of the state and its relations to the wider society. Data from the IMF, World Bank, and OECD, as well as the scholarly literature, demonstrate how rentier governance, fiscal opacity, and the ascendancy of extra-legal priorities have driven Iran’s descent into cycles of stagflation, capital exodus, and institutional regression.

The central challenge is to demonstrate how oil dependency, authoritarian consolidation, the subordination of the Central Bank, and macroeconomic mismanagement have entrenched chronic inflation. Is there a viable pathway to stabilization within prevailing international standards?

The 1979 revolution ruptured Iran’s political economy through pervasive nationalization, state intervention, and the eclipse of the private sector. Subsequent wartime pressures in the 1980s imposed fiscal indiscipline, monetization of deficits, and the emergence of stagflation. IMF and World Bank analyses underscore the role of state-driven money creation in deepening currency misalignment, repressing productive investment, and amplifying vulnerability to external shocks.

The post-war era of the 1990s, despite halting attempts at economic liberalization, failed to establish central bank autonomy or a diversified fiscal base. Successive oil booms fostered populist expenditures, policy volatility, and systemic fragility. The 2000s saw the escalation of the rulers’ nuclear ambitions, regional interventions, and an intensified diversion of public resources to opaque security priorities and proxy networks. Comparative political economy research (Chatham House, Brookings, LSE) documents the erosion of transparency, rising indebtedness, and the subordination of fiscal policy to geopolitical calculation.

The 2010s and 2020s were distinguished by pressures of intensified sanctions, financial isolation, and an aggressive shift toward monetary expansion. Liquidity surges, asset price bubbles, rampant speculation, and the collapse of productive investment coalesced with capital outflows and migration, while public trust and civic participation deteriorated. The “expectations crisis,” marked by generalized uncertainty, defensive economic behavior, and widespread social disaffection, has become self-perpetuating, rendering the inflationary trap intractable.

Price volatility and policy unpredictability have driven capital flight into parallel markets – foreign currency, gold, real estate, and crypto-assets – while undermining confidence in productive investment. Capital has dried up, initiative has eroded, and business as retreated from risk-taking.

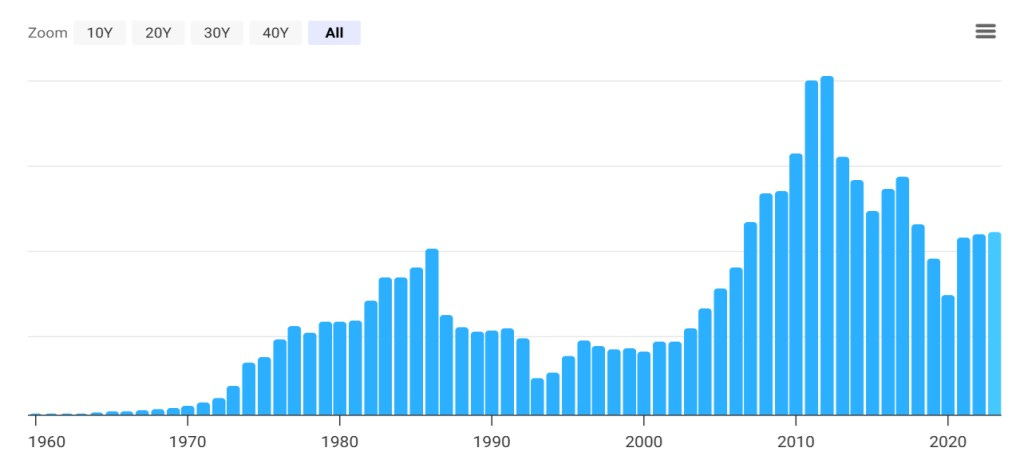

The consequences have been profound – heightened inequality, the collapse of consensus and the breakdown of social cohesion, leading to unprecedented rates of skilled migration and capital outflow. A recent World Bank estimate placed the cost of the brain drain at US$50 billion per year, more than double the value of Iran’s recent petroleum exports, which in 2019 officially amounted to less than US$20 billion. According to data compiled by The Economist, 96 percent of patents registered by Iranian-born inventors between 2007 and 2012 were recorded by Iranians living abroad.

Years of political and economic insecurity—including crackdowns on civil liberties, opaque governance, and enduring economic uncertainty—have pushed many of Iran’s best-educated citizens to seek opportunity abroad. This has led to a sustained loss of skilled professionals, resulting in indirect but serious long-term economic costs for the country. According to recent statistics, nearly 60 percent of Iranian immigrants in the US had at least a bachelor’s degree as of 2019, with more than 30 percent holding a graduate or professional degree. Median household income for these immigrants was nearly $79,000 in 2019—well above the national average. In Germany, nearly half of Iranian asylum seekers had a university degree, a rare figure for a migrant group. This loss of talent is not only a symptom, but also a perpetuating factor in Iran’s structural economic decline.

On the psychological level, sustained inflation has fostered pervasive anxiety, economic conservatism, and a truncated planning horizon. The shift to risk-averse, short-termism entrenches the decay of human capital and the persistence of structural poverty.

The persistence of inflation is attributable to the interaction of several factors, among them heavy reliance on oil revenue, making fiscal sustainability hostage to price shocks. Every disruption in oil export receipts translates into expanding deficits, central bank monetization, and inflationary surges. Second, the government prioritizes geopolitical and nuclear prioritization over economic rationality: A growing portion of state budgets is funneled into costly nuclear projects and regional power projection, subordinating the Central Bank to the imperatives of security policy, subverting institutional independence, distorting monetary governance, and inhibiting policy transparency.

Off-budget expenditures, pervasive security choices, and limited oversight fuel corruption and inefficiency. The lack of public financial data intensifies inflationary expectations and deters both domestic and foreign investment. International sanctions and diplomatic isolation have played a major role, severing access to global finance and destabilizing the monetary and banking systems. Recurring exchange and monetary crises have reinforced the incentives for capital flight and speculative hoarding.

Iran’s chronic inflation has paralyzed economic growth: GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power, has never risen above $8,114 (2012) and has dropped to $4,112 by 2023. This stagnation, compounded by mounting sanctions and the country’s heavy reliance on crude oil and mineral exports, has triggered persistent budget deficits and inflation. Chronic price instability has steadily eroded civic engagement and public trust, while ongoing uncertainty has driven Iranians into herd behavior and speculative safe havens—deepening recession and making real reform ever more elusive.

Collectively, these mechanisms constitute a self-reinforcing architecture of instability and chronic inflation, impervious to superficial or technocratic interventions. Half a century of crisis underscores that stabilization is unattainable without structural transformation rooted in institutional renewal and alignment with international standards of macroeconomic governance.

The prescription for change is complicated and difficult. It has to start with independence for the Central Bank, prohibition of off-budget financing, and compliance with IMF and OECD norms of economic and financial stability, governance, and development, emphasizing fiscal transparency and public accountability.

Comprehensive fiscal reform depends on building a resilient, diversified revenue base, fostering non-oil exports, and rebuilding productive sectors. That requires genuine privatization and competitive markets: dismantling rent-seeking, fostering rule-based business, and corporate governance reform. The government must scale back costly external interventions, focusing on domestic development and pursuing pragmatic, non-ideological diplomacy. It will require robust investments in education, health, and infrastructure and reinvigoration of civic engagement.

Iran stands at a defining crossroads: either embark on far-reaching, transparent, and consensus-based reforms to achieve sustainable development, or remain ensnared in recurrent crisis, stagnation, and accelerated capital and human flight. The window for decisive action is rapidly closing.