By: Amirreza Etasi

This is an autopsy of a century of rupture and decline in Iran’s authentic arts, a decline not built on natural evolution but the product of three successive waves of structural, political, and ideological interventions by ruling governments.

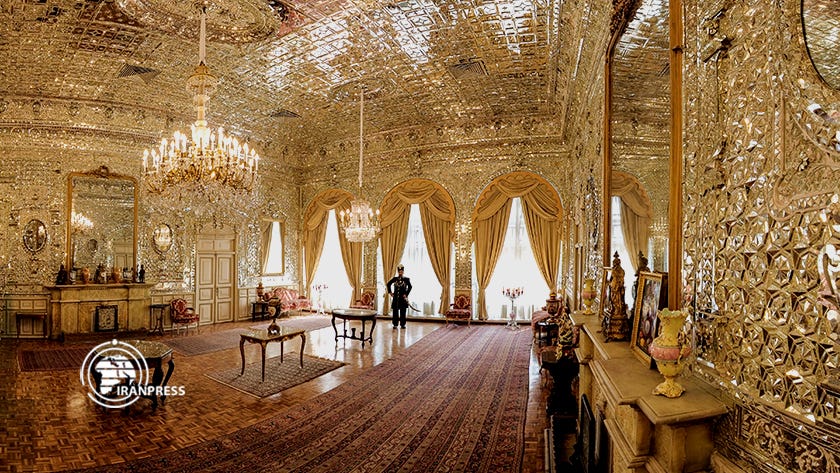

It is a decline built on tragedy. Iran boasts one of the world’s richest art heritages, spanning millennia and encompassing disciplines like architecture, textiles, calligraphy, miniature painting, metalworking, and pottery. It encompasses ancient monumental structures like Persepolis, intricate Safavid-era tilework, Persian carpets, and detailed engraving and marquetry.

They are now in a cage, sometimes adorned with the golden bars of modernization and at other times with the steel walls of ideology. Over the past century, the state has become the primary patron, buyer, and commissioner of art, destroying the independent market and suppressing creativity. The artist is forced to answer to power, not to society.

The direct consequence is a devastating brain drain. The continuous exodus of artistic elites has hollowed out the country’s creative body. This is not a “brain circulation” that enriches the homeland upon return; it is a one-way flight. While this exodus has created a vibrant diaspora—a “second bloodstream” of Iranian art in the pop studios of Los Angeles and the galleries of Paris and New York—it severs the artists’ organic connection to their primary source of inspiration and depletes the cultural capital within Iran.

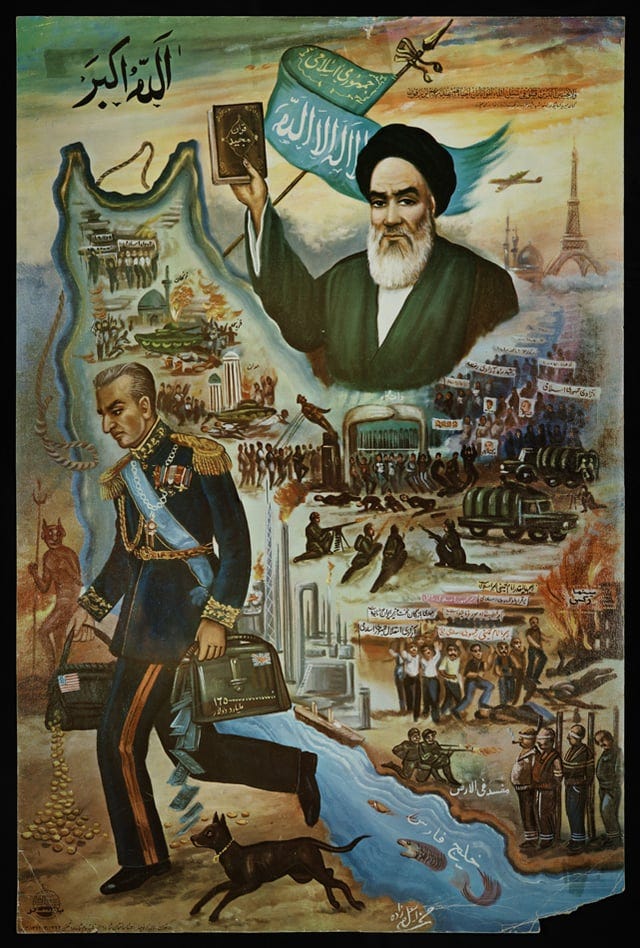

The root of the decline lies in the totalitarian nature of all three of Iran’s ruling ideologies. Whether the archaistic nationalism of Reza Shah, the superficial Westernism of Mohammad Reza Shah, or the religious doctrine of the Islamic Republic, all have been fundamentally at odds with the essence of art, which thrives on plurality, ambiguity, and doubt. By imposing a single worldview, these ideologies have suffocated the space necessary for authentic creation, reducing art to the repetition of state-approved clichés.

The direct consequence is a devastating brain drain. The continuous exodus of artistic elites has hollowed out the country’s creative body. This is not a “brain circulation” that enriches the homeland upon return; it is a one-way flight. While this exodus has created a vibrant diaspora—a “second bloodstream” of Iranian art in the pop studios of Los Angeles and the galleries of Paris and New York—it severs the artists’ organic connection to their primary source of inspiration and depletes the cultural capital within Iran.

The first of these three waves was the “authoritarian modernization” of the first Pahlavi era, which led to a rupture from immediate traditions. The second was the showcase art of the second Pahlavi era, which alienated art from its social context. The third was the cultural engineering of the Islamic Republic, which transformed art into an ideological tool. These interventions severed the traditional chain of knowledge transmission, created a paralyzing dependency of the art economy on the state, and led to the migration of artistic elites, ultimately imprisoning art within the cage of power structures.

In the life of a nation, art is not merely an aesthetic phenomenon. It acts as a sensitive body, a vital sign reflecting the health, dynamism, and internal contradictions of a society. The health of this body depends on an organic bond with its social and historical contexts. When that bond is severed, collective memory and cultural identity are endangered. The fundamental metaphor of Iranian art over the past century is that it has been confined, managed, and engineered by successive power structures instead of growing in free interaction with its society.

Cultural Decline vs. Cultural Transformation

There is an essential distinction between cultural transformation and cultural decline. Transformation is an organic, internal process of renewal. In contrast, decline is an imposed, inorganic state in which an art form loses its vitality, complexity, and connection to its social context. The root of such crises often lies in the nature of the ruling power. When a regime lacks legitimacy, it demotes culture from a site of growth to a tool for social control, and art’s decline begins.

The reality of Iran’s contemporary history is a story of deep and repeated ruptures, the most significant manifestation of which has been the collapse of the master-student apprentice system, the centuries-old bedrock for transmitting arts like music and calligraphy. This system was based on a deep, spiritual relationship.

With the introduction of Western academic models, notably by figures like André Godard, the French archaeologist, architect, and historian who served as the director of the Iranian Archeological Service in the first Pahlavi era, this sacred bond was replaced by a bureaucratic structure of “superior and subordinate.” Art was reduced from a living tradition to an academic subject. This rupture detached art from its intuitive, oral, and practical context, dealing a fatal blow to its organic connection with the native culture.

The reign of Reza Shah from 1925 to 1941 and which established the Pahlavi dynasty marked a fundamental rupture in the history of state intervention in Iranian art. His policies of “authoritarian modernization” were based on two pillars: secular modernism and antiquated nationalism emphasizing a pre-Islamic identity. This dual approach simultaneously targeted religious art and immediate cultural traditions, especially the Qajar heritage, leaving no room for independent creativity.

Architectural Destruction as Cultural Cleansing

One of the most prominent manifestations of this policy was the systematic destruction of historical architecture. These demolitions were ideological acts aimed at cleansing historical memory to build a “new” Iran. In Tehran, the city’s 12 magnificent Qajar-era gates were demolished to develop modern streets. In Tabriz, the Qajar dynasty’s birthplace, valuable structures like the Safavid Aali Qapu Palace were destroyed. This architectural violence severed the people’s visual and emotional connection to their past, transforming art into a state project for building a modern nation-state.

The second Pahlavi era from 1941 to 1979 fostered a bifurcated art world: a modern, elitist scene presented to the West as a showcase of progress and a marginalized realm of traditional arts. The regime’s cultural policies were a contradictory mix of massive investment, selective patronage, and severe political censorship.

The Shiraz Arts Festival (1967–1977), under the patronage of Empress Farah Pahlavi, is the symbolic apex of this “showcase art.” While internationally recognized for its innovative programming in music and cinema, its more radical performances alienated it from the Iranian public. The festival became a symbol of the cultural chasm between a Western-facing elite and the broader society. Events like the infamous play Khook, Bacheh, Atash (Pig, Child, Fire), which featured nudity and simulated sexual acts, provoked widespread public outrage and even a reaction from the SAVAK secret police.

Ultimately, the festival’s symbolic meaning was one of alienation—a performative modernity designed for foreign consumption, not domestic cultural enrichment.

With the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the most radical wave of state intervention began, with the first decade after the revolution marked by extensive purges to cleanse the cultural scene of Pahlavi-era heritage. Art forms were declared haram (religiously forbidden). Dance was completely erased from the public sphere, and the Iranian National Ballet was dissolved.

Sculpture faced a decade of silence, with many Pahlavi-era statues destroyed as symbols of tyranny. Music was suspended, pop was banned, female voices were silenced, and even traditional music faced severe restrictions. Many prominent artists fled into a massive exile, while those who remained, like Mohammad-Reza Shajarian and Mohammad-Reza Lotfi and Hossein Alizadeh and the Chavosh group, fought to keep the flame of authentic music alive.

From the 1990s, the state shifted from elimination to active “cultural engineering,” a paradigm of designing and directing the entire cultural system based on an ideological ideal. This policy, a clear example of what the Italian philosopher and antifascist Antonio Gramsci termed cultural hegemony, aimed to manufacture consent by propagating state-approved values through cultural institutions. It created a deep dichotomy: a well-funded “official-commissioned art” and a precarious “independent or underground art.”

The state’s cultural bodies effectively became what the French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser called Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs), using art not for expression but for reproducing the ruling ideology. This was particularly evident in the post-2000s, as state-run media (IRIB) and government-funded events like the Fajr Festivals began promoting an “ideologically sanitized” pop music to compete with the popular but un-Islamic exiled pop scene based in Los Angeles.

The Legacy of Rupture

The impact of these interventions is visible across all artistic disciplines. This state capture of art is not unique; similar processes occurred in Stalinist Russia and post-1949 China, where art was mobilized as state propaganda. Yet Iran’s case differs in its potent fusion of political power with metaphysical legitimacy, making the state’s ideological grip uniquely pervasive.

The rupture in the master-student system weakened the intuitive and improvisational essence of traditional music. After the revolution, the 1980s saw an unprecedented recession in music. While artists like Lotfi and Alizadeh and Shajarian and Meshkatian produced seminal works that captured the social mood, the overall landscape withered. In later decades, the rise of state-managed pop music often led to a decline in auditory taste. Today, traditional music faces a crisis of innovation, trapped in repetition and unable to engage in the “creative destruction” necessary for growth.

Sculpture’s fate mirrors Iran’s political trajectory. A tool of royal propaganda under the Pahlavi dynasty, it was nearly eradicated after the revolution as a symbol of tyranny and idolatry. Its managed return came primarily in the form of state-commissioned war memorials, transforming it into a functional, ideological art. Similarly, mural painting, a powerful medium of popular protest during the revolution, was quickly co-opted by the state to serve as official propaganda.

The destruction of historical buildings during the first Pahlavi era fueled a deep identity crisis in architecture. Cities became a chaotic museum of unrelated styles: neoclassical imitations next to archaistic fantasies and traditionalist reproductions. This rootless eclecticism, born of ideological contradictions, prevented the formation of an authentic contemporary architectural language and left an enduring legacy of visual incoherence.

Dance was the ultimate victim. Declared haram, it was completely erased from the public sphere, its institutions dismantled, and its artists forced into exile or silence. Cinema, however, was recognized as a strategic tool of power. Both the Pahlavi and Islamic Republic regimes heavily invested in and censored cinema to propagate their respective ideologies, from promoting a Westernized lifestyle to disseminating revolutionary values. Its growth was not organic but engineered. Art as a Tool of Power

A common thread links all three regimes: an instrumental view of art. In each period, art was weaponized for propaganda, legitimization, and social control. Art lost its pulse. The state dictated its heartbeat. An art form intended to be the vigilant conscience of society was demoted to its mouthpiece, its mission of “expressing truth” subverted to the function of “consolidating power”.

The Prospect of Art Freed from the Cage

The autopsy of a century of Iranian art reveals a bitter narrative of creativity subjugated by power. The observed cultural decline is not a story of the inherent failure of Iranian art or artists, but a story of the success of ruling powers in instrumentalizing and controlling one of the most vibrant dimensions of social life.

Authentic art, in this sense, is not a nostalgic return to tradition, nor a nationalist essentialism, but the free unfolding of creativity within the moral and historical consciousness of a people. It is an art that breathes with its society, not for its state.

Freeing art from this cage requires fundamental transformations that go beyond superficial policy changes. It depends on the independence of cultural institutions, the formation of a dynamic private art economy, the guarantee of free expression, and the re-establishment of the broken link between art, history, and society. Only then can Iranian art escape the tight cage of ideology and politics and play its true role as the vigilant conscience, the true mirror of society, and a force for the cultural transcendence of a nation.

Amirreza Etasi is a regular contributor to Asia Sentinel. He has served in management roles in Iran’s oil and gas sector, while contributing in-depth analysis to Middle Eastern publications. He can be reached at Amir.etasi@gmail.com.

this is very tragic. ..

how i wish that my ancestral homeland would be free from western domination and the iron cage of ideology and power (and its own elites as well).

Very tragic. Iran is one more instance of an ancient society getting pulverised under the impact first of Western domination and second by the reaction by its own elites.