Indonesia’s High-Speed Rail Time Bomb

‘Whoosh’ Plagued by construction overruns and unrealistic revenue and passenger projections

By: Ainur Rohmah

Indonesia’s first high-speed rail line connecting Jakarta with Bandung in West Java is now staring at a financial abyss. Saddled with heavy debt repayments to China and burdened by high operating costs, the company has been bleeding trillions of rupiah.

Even as the line, known as Whoosh, has reduced travel time on the 142-km run from three hours to 40 minutes and has transported millions of passengers, ticket revenue and passenger projections have fallen far short of covering the massive expenses.

Touted as Southeast Asia’s first bullet train, the project, a China-Indonesia joint venture known as PT Kereta Cepat Indonesia China (KCIC), was once heralded as a symbol of Indonesia’s modernization. But today, it has turned into a source of persistent trouble. Debt obligations have ballooned to Rs116 trillion (US$6.974 billion), placing not only KCIC in jeopardy but also dragging down four state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that hold majority shares in the operator.

KCIC itself has never published its financial reports. Yet the extent of the bleeding can be traced through the filings of its parent companies. The largest is PT Kereta Api Indonesia (KAI), which also controls the majority of shares in PT Pilar Sinergi BUMN Indonesia (PSBI), the consortium that holds most of KCIC. PSBI’s members include KAI, with 58.53 percent of the shares; PT Wijaya Karya (Persero) Tbk, with 33.36 percent; PT Jasa Marga (Persero) Tbk, with 7.08 percent; and plantation company PTPN VIII, with 1.03 percent.

Together, these state-owned firms are being forced to shoulder the snowballing losses. According to KAI’s unaudited financial statement as of June 30, published on its official website, PSBI suffered a loss of Rp.4.195 trillion throughout 2024. The losses didn’t stop there. In just the first six months of 2025, PSBI bled another Rp.1.625 trillion.

As the largest shareholder, KAI bears the biggest portion of these losses, absorbing Rp.2.24 trillion in 2024 alone. In the first half of 2025, the company’s share of the burden was another Rp.951.48 billion. In addition, KAI was forced to set aside a sinking fund worth Rp.1.455 trillion in 2024 – money that can be withdrawn at any time should Whoosh require another bailout.

“This is a time bomb,” KAI’s president director, Bobby Rasyidin, told lawmakers in a recent parliamentary hearing. “We (KAI) could have been profitable. But because of the Whoosh debt, we are in deficit.” He added that KAI was coordinating with the Nusantara Capital Investment Management Agency (BPI Danantara) “to find solutions for the debt problem of the high-speed rail project.”

Although originally the project was estimated to cost $6.02 billion, over time, that ballooned to US$7.22 billion, three-quarters of which was financed through loans from the China Development Bank, amounting to US$5.415 billion. With interest rates of 2 percent per year on the principal loan and 3.4 percent on the cost overrun portion, KCIC owes US$120.9 million annually.

The challenge grows heavier because KCIC is struggling even to cover operating costs, let alone debt repayment. Passenger numbers remain below projections, leaving the company unable to service its loans. That has triggered discussions about shifting KCIC’s debt obligations to its parent state-owned enterprises which in turn have been folded into President Prabowo Subianto’s controversial Danantara sovereign debt vehicle. If these SOEs themselves begin to suffocate under the financial weight, the burden would inevitably land on the state budget.

Danantara is reportedly exploring mechanisms for restructuring Whoosh’s debt to prevent further pressure on KAI. Danantara’s Chief Operating Officer, Dony Oskaria, said no final decision had been reached on how to settle the rail’s Rs116 trillion debt and interest. He stressed that the issue had already been written into this year’s corporate work plan and budget. For both Danantara and KAI, resolving the Whoosh problem has become a top priority.

Controversial From the Start

The Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Rail was launched during the administration of President Joko Widodo, who inaugurated it on October 2, 2023, with commercial operations beginning on October 17, 2023, under the brand name Whoosh.

From the very beginning, the project was marred by controversy. Even before construction began, Ignasius Jonan, who served as transportation minister between 2014 and 2016, voiced strong opposition to the plan, which ultimately cost him his cabinet post. As a former president director of KAI, Jonan argued that the Jakarta-Bandung carried multiple flaws commercially, technically, and operationally.

He said that building a high-speed line for such a short route was an example of overconcentration on Java, the nation’s most developed island. Technically, he argued, trains capable of running at speeds above 300 kilometers per hour were ill-suited for the mere 150-kilometer distance between Jakarta and Bandung. High-speed rail, in his view, was better suited for long-distance corridors, such as Jakarta-Surabaya.

But such routes would require astronomical investment, which he considered unnecessary given other urgent infrastructure priorities. Spending public funds on a short line, he warned, would only deepen the perception of Java-centrism in development.

Jonan also rejected any use of state budget (APBN) funding for the rail. He withheld approval for the proposed route, citing a problematic concession arrangement: KCIC wanted the concession to last 50 years starting from the rail’s operation, while existing regulations required concessions to begin from the signing of the contract. In the end, the government not only relented but extended the concession to 80 years.

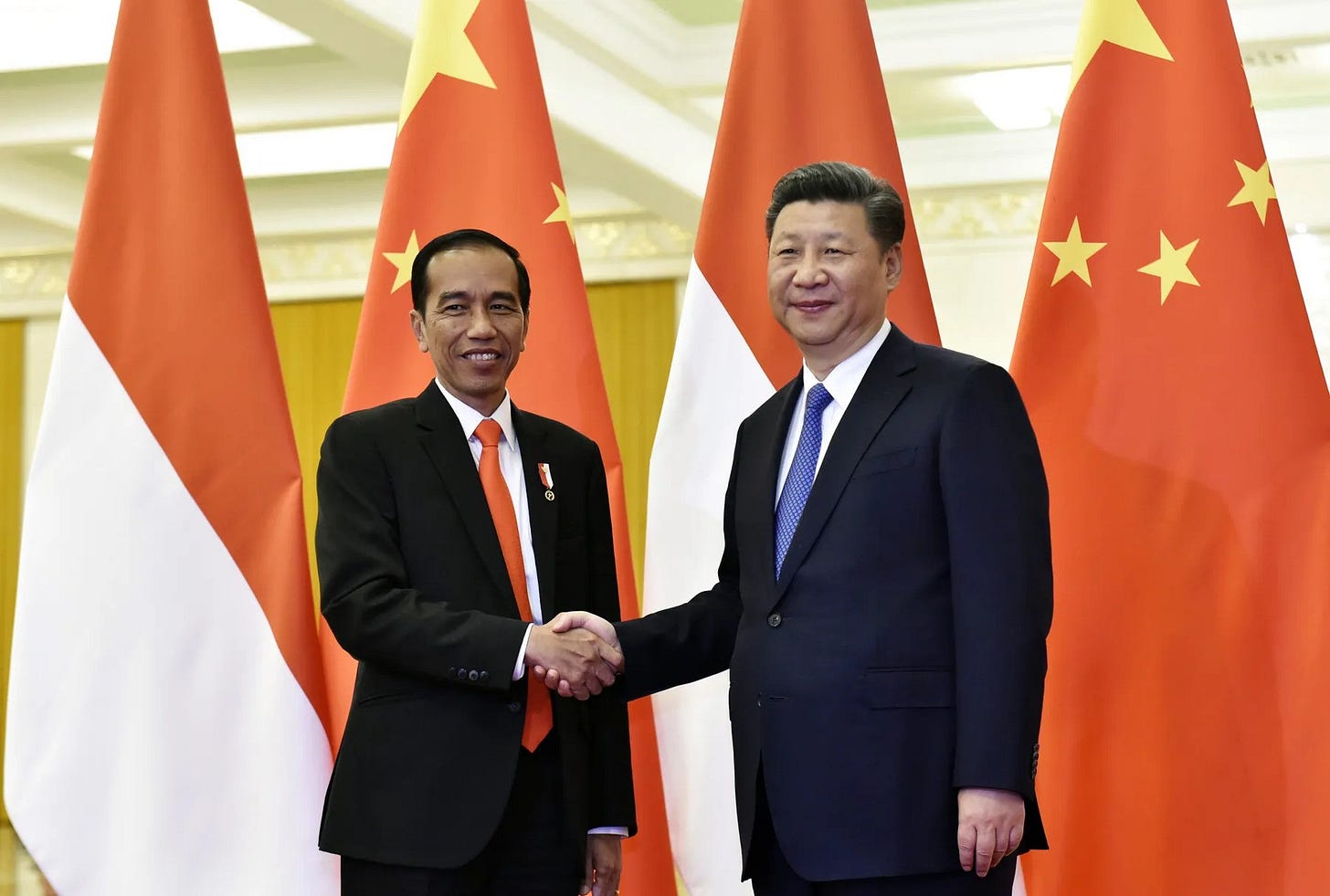

On financing, many had already cautioned that Indonesia risked falling into China’s debt trap. Jokowi, however, brushed aside such warnings. When he launched the project in 2016, he promised that the high-speed rail would not burden the state budget, as it would be financed through a business-to-business scheme between Indonesian and Chinese SOEs.

The government, the president said, wouldn’t disburse public funds or provide guarantees, even if the project ran into trouble. Most of the financing would come from China Development Bank loans.

But that promise soon unraveled. The government began injecting capital into KCIC through state equity participation in KAI. By September 2023, it went even further, opening the door for the state to guarantee the project’s loans, made official through a regulation signed by then Finance Minister Sri Mulyani, allowing state guarantees for Whoosh’s debts.

Debt Trap

A report by Australia’s Lowy Institute in May found that the world’s 75 poorest nations owed China a combined $US22 billion in what it called a “debt wave.” Over all, in 2025 alone, China is expected to collect US$35 billion in repayments from projects cross the world. According to the report, these debts are largely the result of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has funded projects in developing nations ranging from schools and transport infrastructure to hospitals.

By 2016, China had become the world’s largest bilateral lender, disbursing US$50 billion that year alone. Indonesia is among the borrowers, with Whoosh one of the flagship projects tied to Chinese financing.

Today, the BRI is increasingly criticized as a trap ensnaring developing and poor countries in loans they can’t repay. It typically begins with Beijing offering to co-finance a single project. But as repayment becomes unmanageable, debtor nations are often forced to hand over assets to China. Analysts have dubbed this phenomenon “hidden debt,” describing how seemingly friendly financing partnerships turn into heavy debt burdens that strip countries of leverage and resources.

After many decades of "Asian capitalism" experiments, here's another glaring failure of "Asian" state capitalism's failure. It's a grotesque waste of increasingly crucial public funds being blown by corrupt and incompetent, in this case long after the miserable failure of Pertamina, Indonesia's political and bureaucratic class. Whilst the latter enrich themselves via shady business deals, direct corruption and kleptocratic tendencies, the people who break their backs every day for a miserable dollar that often gets siphoned by tax authorities and crooked and greedy business owners are left to rot in the hells created by cretinous politicians. Turun Prabowo Subianto! Turun sekarang!

A Jakarta resident also told me the train is even more useless because it does not actually take you to Bandung but to an area one hour away from downtown Bandung, making it even more ridiculous and useless. It will never earn a profit. Ever .