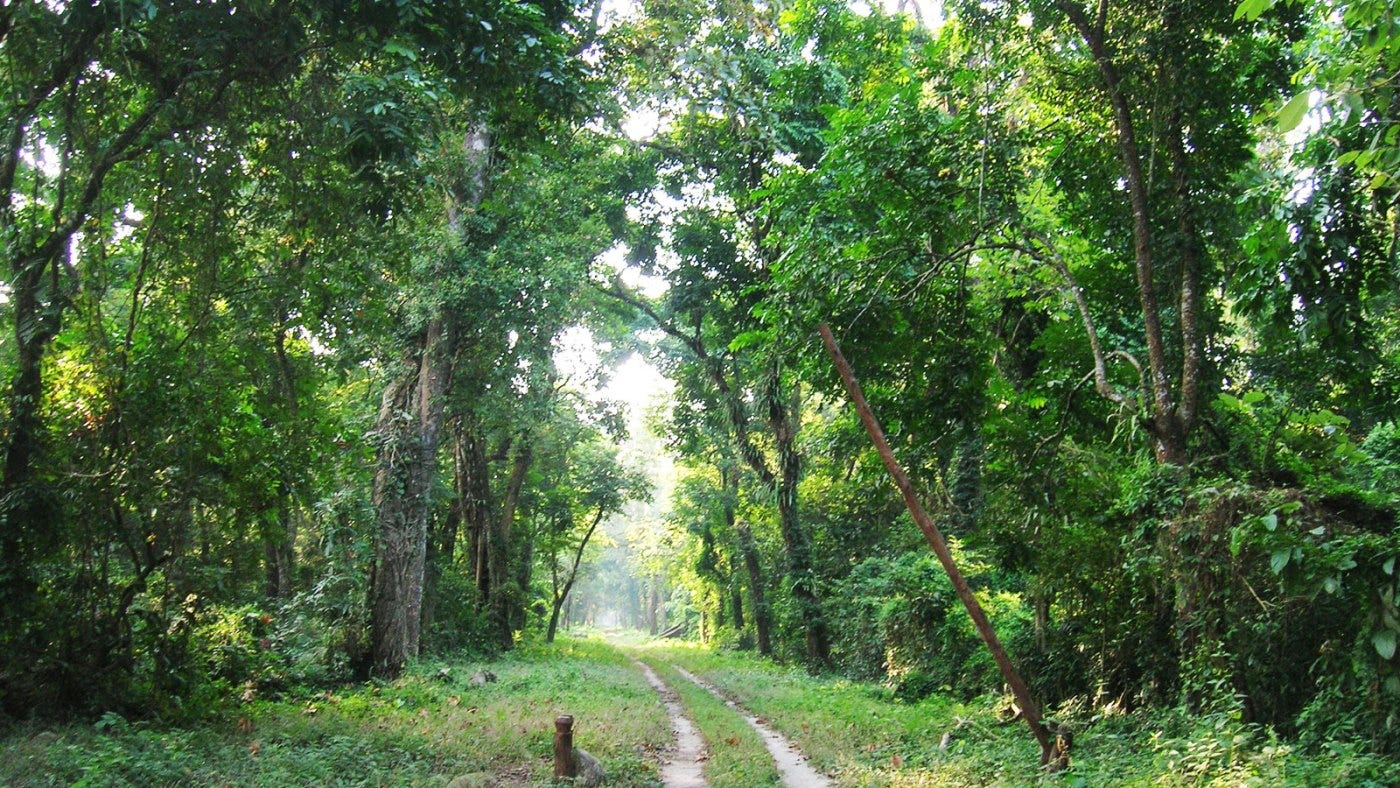

India’s ‘Amazon of the East’ Under Threat from Development

Public outcry stops development of open-face coal mine

By: Nava Thakuria

Public outcry has led to the suspension of an open-face coal mining operation in Northeast India’s Dehing Patkai Elephant Reserve, a huge area of tropical rainforest on the south bank of the Brahmaputra River that is known as the Amazon of the East. It lies under the Eastern Himalaya mountain range, an Indo-Burma global biodiversity hot…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.