India Election to Test Modi’s Vote-Winning Power

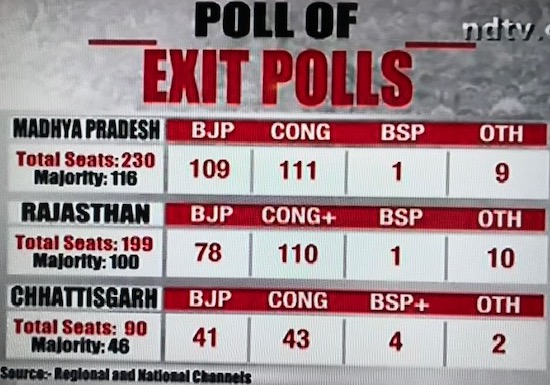

UPDATE: Exit polls published on Dec. 7 for assembly elections indicate that the Congress Party might be doing significantly better than had been expected.

The figures are averages calculated by the NDTV television news channel from exit polls conducted by a number of organisations, whose results varied very widely. The actual results will come on Decembe…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.