India’s BJP Hangs Onto Power but Loses Overall Control

Big setback for Modi’s aim to establish himself as invincible leader

By: John Elliott

The face of Indian politics has changed dramatically with an unexpected resurgence of opposition regional parties and the Gandhi-led Congress Party, and declining support for Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Although Narendra Modi looks set to become prime minister for a third term, his dreams of winning a dominant personal victory as a supreme leader have therefore been shattered in one of the most unexpected reversals for many years – a result that proves the strength and power of India’s often criticized parliamentary democracy.

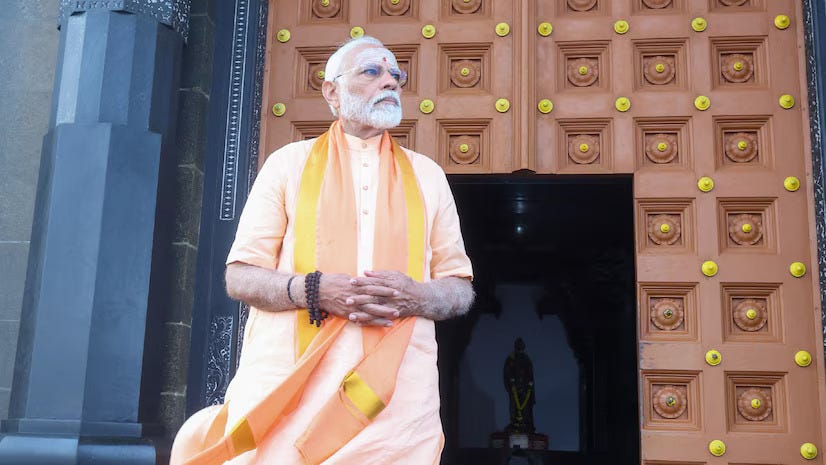

His personal pitch of projecting himself with an almost priestly Hinduism religious role seems to have failed to attract votes – it even failed in the constituency that contains the Ayodhya temple where he presided in January and where the BJP parliamentary candidate looks like losing.

By early evening in India, the results, and trends in constituencies not yet declared, were 292 seats in the Lok Sabha (lower house of parliament) for the BJP’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA), and 232 for the I.N.D.I.A grouping that includes the Congress party, plus 19 for other parties. Those figures included 239 for the BJP, down 64 from 303 in the 2019 election, and 100 for Congress, up 48 from 2019.

The BJP has therefore failed to reach the 274-majority mark so must rule with coalition partners for the first time since it came to power in 2014. That will pose a personal test for Modi, who has run a centrally controlled government from his prime minister’s office with little notice being taken of alliance partners or other interests.

There has been some suggestion that two regional coalition partners might switch to support the I.N.D.I.A, which would remove the NDA’s majority and could prevent Modi from forming the government. That, however, seems unlikely. The parties are Bihar’s Janata Dal United (JDU) led by Nitish Kumar, which looks like getting 12 seats, and Andhra Pradesh’s Telegu Desam led by Chandrababu Naidu with 16. Both leaders have at different times supported and not supported the BJP but Kumar has said he will attend a meeting of NDA leaders in Delhi tomorrow.

The overall result vindicates the hopes of Modi’s opponents that one day the political pendulum would swing against harsh autocratic Hindu nationalism. Till today, that seemed only a hope for the somewhat distant future – scarcely anyone had expected it to happen in this election.

Part of the BJP’s problem was that there was no clear focus in its election campaign, apart from the presence of Modi, and there was a lack of firm policies for the future. This means that local issues and the role of regional parties became important in many constituencies. It was also the first time that Modi had faced a united opposition. Turn-out was low compared with earlier elections, suggesting that some BJP supporters had not voted, partly because they felt that the government had not done enough to boost employment and curb price increases of basic goods. It is also possible that many voters did not like the extreme anti-Muslim tilt of Modi’s campaigning.

It also seems that the Modi wave that began in 2014 may have peaked. In his own constituency of Varanasi, he won with a majority of just 152,513 votes, – down from 471,000 in 2019.

“Big decisions”

Modi is presenting the result as a victory for Indian democracy and a success for the BJP winning a third consecutive term with a sizeable majority over the I.N.D.I.A. Speaking at a BJP rally when the results were clear, he said the government would now write a “new chapter of big decisions.”

That underlines the point that, while he might feel less confident about pushing Hindu nationalism and sidelining Muslims as a religious minority, he will now want to do more on economic reforms, social support systems for the poor, attracting foreign investment, and building new technology-oriented industries.

In addition to failing to establish a countrywide endorsement for his leadership, Modi also failed to galvanize support in southern states where he wanted the BJP to establish a presence. It only won one seat in Kerala and none in Tamil Nadu. But the BJP did repeat its success in Delhi where it won all seven parliamentary seats, as it did in 2019.

In the state assembly election in Orissa, it won control for the first time, pushing out the state-level Biju Janata Dal led by Naveen Patnaik, who has been chief minister for 24 consecutive years, the second longest of any chief minister in the country.

The BJP’s biggest setbacks that helped to swing the overall result came in two states. The biggest surprise was Uttar Pradesh where the I.N.D.I.A grouping won 44 parliamentary seats whereas the NDA won only 35. This was unexpected because Yogi Adityanath, the Hindu priest-turned-chief minister, was reported to have built a good image for the BJP by strengthening law and order and boosting both development projects and care for the poor. The result was a victory for Akhilesh Yadav, leader of the regional Samajwadi Party, working with Rahul Gandhi of the Congress party.

Observers suggest that Yadav and Gandhi successfully worried members of India’s lowest castes that reservation schemes which provide them with jobs and other advantages might be canceled by the Modi government amending the constitution.

In West Bengal, the reigning chief minister, Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress saw off the challenge and her party won (or is winning) 18 parliamentary seats compared with the BJP’s four. This was a major setback for Modi who wanted to establish the BJP as a significant political force in the state.

The overall result was especially surprising coming after exit polls published when voting ended on June 1. These indicated a massive swing in favor of the BJP with 355 to 380 seats. That led to a surge on the Indian stock market with prices reaching record levels and a crash when the actual results began to appear.

But the markets need not have worried. The results may not impede the government’s plans for economic development and should, as Modi has said, lead to renewed efforts to continue India’s development as the world’s third largest economy.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He logs at Riding the Elephant.