The Gold Price and the Current Turmoil

Many central bankers sold for 6 decades, now regret it

By: Philip Bowring

Of the many crazy aspects of the world in mid-2025, the one that reflects all the others is the price of gold. As in previous such periods of political and economic instability, the gold price is eagerly followed in the media as central banks follow the herd and show their own lack of faith in currencies by building up gold reserves. These have now surpassed the euro as the world’s second largest reserve asset, with big buyers including the likes of Turkey and Poland, as well as long-time buyers Japan, China, and India.

At one level, this is hardly surprising. The US dollar is destined for seemingly endless deficits, but large and liquid alternatives are not easy to find. Meanwhile, millions of people are taking refuge in cryptocurrencies, most notably the Stablecoins, which are supposedly backed by impeccable liquid assets and are a dream come true for money launders and criminal activities. They exist on a public ledger, but as they pay no interest, they are a gold mine for the issuers who collect interest on the Treasury securities which back them. Whether they are fool’s gold remains to be seen.

But meanwhile, those who look at the physical metal as a safe bet alternative to cryptos and old-fashioned currencies might do well to look at some of the statistics.

The first one that should jump out is this: the US dollar price of gold has increased tenfold since 2002, when it was languishing below US$300 an ounce. In that time, consumer prices (as measured by the US CPI) have only doubled. A long period in the US$250 range prior to 2003 persuaded the British government to sell half its holding, now leaving it with US$30-40 billion less than it would have had just by holding on. Yet buying at 10 times that price may be equally foolhardy.

In the short run, the price is determined by a combination of sentiment and global liquidity. Massive dollar surpluses always find a home. New supply is also small and inelastic relative to the total stock of gold in existence. Yet at some point, as in the past, two things can change. One is supply itself. The gap between production cost and market prices is now so high as to not only spur increased output by existing mines, whether through enabling the processing of lower-grade ores, or just generally ramping up production. As is currently being seen in some parts of Africa, prices are such as to reward illegal and inefficient artisanal mining. For established producers, it is estimated that the current cash costs – labor, processing, machinery, royalties, etc – now run around US$800-900. Looking to the longer term, the all-in costs are estimated at about US$1,400. All-in costs add the costs of exploration, mine development, etc, to the cash costs. If it is assumed that the price will stay at or above the US$3,000 mark for the next several years, the potential for a sustained surge in output is clear.

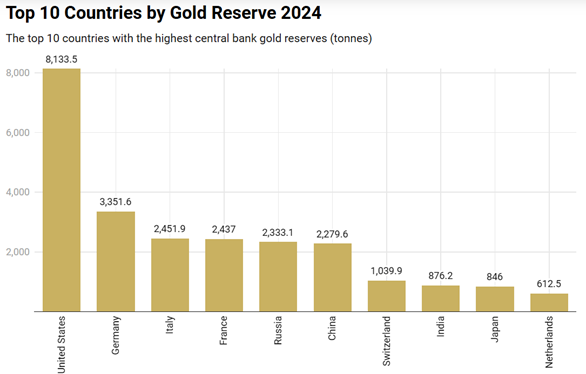

However, the recent surge in central bank gold buying may hide the fact that for 60 years, they had been net sellers of gold. Official gold holdings peaked at 38,000 metric tonnes in the mid-1960s when the Bretton Woods system of a fixed dollar/gold exchange rate (US$35 an ounce) existed. They are now back to 36,000 tonnes. Thus, the main reason for the increased role of gold in international reserves has been its increase in price. At least on paper, this has increased the clout of big holders US, Russia, Japan, China, India, Germany, and other EU countries, while most of the developing world has very little. In east Asia, Singapore is a significant holder with 215 tonnes but has recently been a seller of 4.8 tonnes. Another big recent seller has been Uzbekistan of 14 tonnes, while neighboring Kazakhstan bought 6.4 tonnes (all data via World Gold Council). Increasing amounts of gold are held by Exchange Traded Funds on behalf of individuals, which is fine for a broad investment portfolio, but not much use for those in a crisis needing the metal itself to buy food or freedom.

Predicting where the gold price will go from here is anyone’s guess. But it is worth reflecting on past spectacular moves: from US$50 in 1970 to US$850 in 1980, then down to US$270 in the 2000s, and so far in 2025 rising from US$2,606 to US$3,390. So, how now does the gold risk compare with, for example, Indonesian or Philippine government bonds yielding 5.5-.6.5 percent or major Chinese state banks with 11 percent dividend yields? Go figure.