By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

US President Donald Trump’s confrontational policies, rather than pushing America’s trade allies toward China, are pushing them away from single-country dependence altogether, and that should worry Beijing, too. China is winning market share but might be increasingly losing its centrality. The trade agreement between the 27-country European Union and India deal, signed on January 27 and celebrated as the “mother of all deals,” was sold in Europe as protection against US unpredictability. Its real impact, however, may be felt across Asia.

For decades, Asian supply chains have been built around China as the unavoidable hub. While acknowledging deep structural problems and latent protectionism on both ends, this agreement disrupts that logic. Spanning nearly a quarter of global GDP and a third of world trade, it elevates India as a credible alternative node, both for EU and Asian economies, in the global economy. For Asian economies, the message is stark: the era of unavoidable reliance on Beijing may be ending.

New Economic Axis: How India Is Elevated

The EU–India agreement represents far more than a classic market-opening deal. After nearly 20 years of negotiation, the pact liberalizes trade on most goods and services between the EU’s 27 member states and India’s big domestic economy. Under the terms, tariffs on 96 percent of EU goods will be reduced or eliminated, with similar reductions applied to Indian exports into the EU, including textiles, engineering goods and marine products. European carmakers, long restricted by India’s punitive import duties of up to 110 percent, will see these levies fall in phases to as low as 10 percent, expanding their access to India’s fast-growing automotive market.

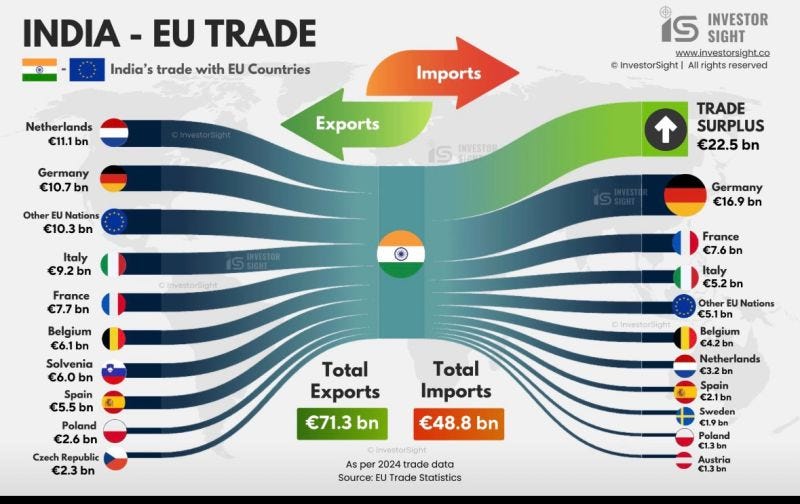

India’s strategic value to Europe is underscored by size: together the EU and India represent about 2 billion consumers and roughly 25 percent of global GDP. Bilateral goods trade already exceeded €180 billion in 2024, and analysts project EU goods exports to India could nearly double by 2032 as tariff barriers come down and regulatory procedures are streamlined and relaxed.

But beyond the numbers lies strategic calculus. Europe sees the agreement as a hedge against economic volatility in North America and China, while India gains privileged access to Europe’s high-value markets and advanced regulatory frameworks—especially in sectors where meeting EU standards can unlock global value chain participation. The pact also tackles non-tariff barriers and includes commitments on investment protection, intellectual property and sustainable development, signaling a depth beyond traditional free trade agreements.

Asia’s Strategic Crossroads

This geography of trade has direct implications not only for India but for Asia overall. For much of this century, Asia’s exporters—for example, Japan and South Korea—have organized their production significantly around China’s central role in global supply chains. China’s vast manufacturing base, coupled with access to international markets, made it the indispensable hub for intermediate goods, particularly in electronics, automotive and battery sectors. Although data vary across industries, recent reporting shows China still accounted for a substantial share of intermediate inputs and final goods exports for its neighbors, reflecting entrenched interdependence.

South Korea, for instance, has seen its share of intermediate goods imports from China rise over the past decade, even as the structure of trade evolves. Japan remains deeply linked: Chinese markets absorb roughly a quarter of Japan’s machinery and automotive exports, while China supplies a large share of intermediate components for key Japanese industries. These patterns have shaped decades of investment and production decisions. With few exceptions, very similar patterns exist throughout most of Asia.

The EU–India deal introduces a credible alternative. India admittedly has a long way to go to build the manufacturing and supply chain base to rival China, with complex regulatory compliance, red tape, severe infrastructure bottlenecks, intense price sensitivity among consumers and logistical delays in shipping and customs clearance. But by aligning regulatory and quality standards with the EU, known for some of the world’s most exacting compliance requirements, India has the potential to eventually become a third anchor for supply chain diversification.

Firms in Japan, South Korea and beyond have the potential to leverage the agreement to shift segments of production to India without sacrificing access to European markets. In practice, this means not just exporting final goods to the EU, but participating in mutually reinforcing supply networks where India aggregates inputs and meets regulatory benchmarks acceptable in European value chains.

Moreover, Japan and South Korea face distinct strategic dilemmas. Both have felt the impact of changing Chinese demand structures: South Korea’s export share in China has declined in certain segments even as overall dependence remains high. Meanwhile, Japan’s industrial base continues to source critical intermediate goods from across East Asia. For these economies, India’s elevated role offers diversification, not isolation—a strategic buffer against both US and Chinese trade volatility.

Take electric vehicle batteries, pharmaceuticals, and green energy technologies: these are sectors where regulatory compliance is both a market prerequisite and a source of competitive advantage. Indian production that satisfies EU standards can now be integrated into regional supply chains in ways that had previously required intermediary transformation in China. The result is reduced exposure to Chinacentric supply routes—and lower risk from geopolitical disruptions or trade frictions. This is especially useful for states in Asia that must navigate trade ties with China without sacrificing their claims to certain territories and regions in the South and East China Seas. Reduced exposure to China could give these states more leeway vis-à-vis Beijing’s unilateral claims on these regions.

The deal also comes at a time of mounting external pressures. US protectionist measures have roiled global trade decision-making, prompting many countries to hedge and diversify. With the EU and India moving closer, Asian exporters will take note—and adapt.

Competitive Pressures and the New Regional Economy

The EU–India agreement will not only reshape supply chains, it will also intensify competition. Indian exporters are poised to gain zero-tariff access in key categories such as textiles, leather, gems and jewelry, sectors that traditionally face stiff external competition. With reduced barriers, Indian firms could expand market share in Europe at the expense of regional competitors such as Bangladesh and Pakistan that had previously benefited from preferential access arrangements. For instance, despite Pakistan’s GSP Plus status, which allows duty-free access for nearly 80 percent of its exports to the EU, the country’s textile exports stand at US$6.2 billion, marginally ahead of India’s US$5.6 billion in exports even though the latter faces a 12 percent tariff. With the new pact, India is therefore well poised to dominate.

At the same time, European firms will bring competitive pressure into India’s manufacturing landscape although importers will be forced to fight the fearsome protectionism built into Indian culture. Reduced tariffs on machinery, automotive parts and high-precision equipment could accelerate technology transfer and productivity growth, but also challenge local producers who have long operated behind protective walls. These competitive dynamics can be expected to eventually ripple across Asia as firms in Japan, South Korea and ASEAN reassess where to invest and how to position themselves in a shifting hierarchy of production hubs.

For Asian policymakers, therefore, the practical question is how to integrate this new axis into broader economic strategies. Will they pursue deeper partnerships with India to secure diversification? Will they adapt domestic industrial policies to capture new opportunities in India–EU value chains? These are decisions with long-term implications for growth trajectories and geopolitical alignment.

Moment of Choice for Asia

For much of the past two decades, the idea of an “Asian century” has been shorthand largely for China’s rise. Growth, trade integration, and industrial upgrading across the region were structured around China’s centrality to global markets. The EU–India trade deal complicates that assumption. By elevating India as a regulatory-compliant manufacturing and investment hub connected directly to Europe, the agreement creates space for a more distributed Asian economic order.

Whether this moment produces a genuinely Asian century will depend on how regional economies respond. Japan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia now have an opportunity to diversify supply chains, co-invest in India’s industrial expansion, and reduce excessive dependence on any single market. If they succeed, Asia’s growth story could shift from one of hierarchical dependence to one of plural centers of production and influence. The EU–India corridor does not diminish China’s importance, but it does offer Asia a chance to rebalance. Taken together, that rebalancing may determine whether the coming decades belong to one dominant power, or to a more resilient and collective Asian century.

Dr Salman Rafi Sheikh is an Assistant Professor of Politics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) in Pakistan. He is a long-time contributor on diplomatic affairs to Asia Sentinel.