End Nears For India’s Maoist Rebellion

Despite flawed methods and focus on armed revolution, rebellion focused attention on deep inequalities and uneven governance

By: Nirupama Subramaniam

As 2025 draws to a close, the Modi government has declared that with the arrests, surrenders or killings of several top Naxalite/Maoist cadres, the insurgency termed in 2009 by then-Prime Minister Manmohan Singh “the greatest internal security threat to our country” to be on its last legs. Speaking on September 28, Union Home Minister Amit Shah, in charge of internal security, asked the cadres still active to surrender or face harsh action, with March 31 “the date set to bid farewell to Naxalism from this country.”

“Some people have called for talks, Shah said. “Let me make it clear again that both the Chhattisgarh and central governments are committed to development across [...] all Naxal-affected areas. What is there to talk about? A lucrative surrender-and-rehabilitation policy has been put in place. Come forward and lay down your weapons.” He asked people in Maoist strongholds to persuade the youth in their villages to lay down arms.

At its peak 15 years ago, the insurgency affected 180 of 624 districts in Chhattisgarh, with the guerillas dominating large portions of them, many thickly forested, where the population comprises mainly communities of Adivasis, India’s indigenous people, officially known as Scheduled Tribes, impoverished, deprived and long neglected by both the federal and state governments. They were a ready catchment for recruits to an insurgency that promised to overthrow the state.

In mid-October, the Union Ministry of Home Affairs said the number of districts where insurgents had strongholds had come down to 11 from 18 earlier in the year. Shah said 270 Naxal cadres had been killed this year, 680 arrested, and 1,225 surrendered by the end of September, when he spoke.

The spread of “left-wing extremism” or LWE as Naxalites/Maoists are officially described, goes back to the 1960s, when factions of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) rejected the party’s participation in India’s parliamentary democracy, and borrowing from Mao, urged “protracted war” to overthrow the state and restore power to the people. Launched as a violent revolt by poor peasants in the Naxalbari district of West Bengal (from where Naxalites got their name), the promise of its radicalism seduced young students, drew the sympathy of some intellectuals and found echoes in art, cinema and literature. The violence spread from the rural areas of West Bengal to the state capital Kolkata, before it was put down brutally by the state.

Then it gained new life in Andhra Pradesh in south India, among landless peasants agitating for land reforms. A new party was formed, called Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) People’s War, or simply People’s War Group, which later became CPI (Maoist). By 1980, a new generation of local leaders took up the baton in what is present day Telangana, tuned the ideology to fit the geography, strengthened it organizationally, with foot soldiers taking it to the people in remote areas. They looted weapons from the police, made them too in their own underground factories, or procured them from smugglers on India’s eastern borders. In 2000, the guerillas organized themselves into a proper armed wing called the People’s Liberation Guerilla Army.

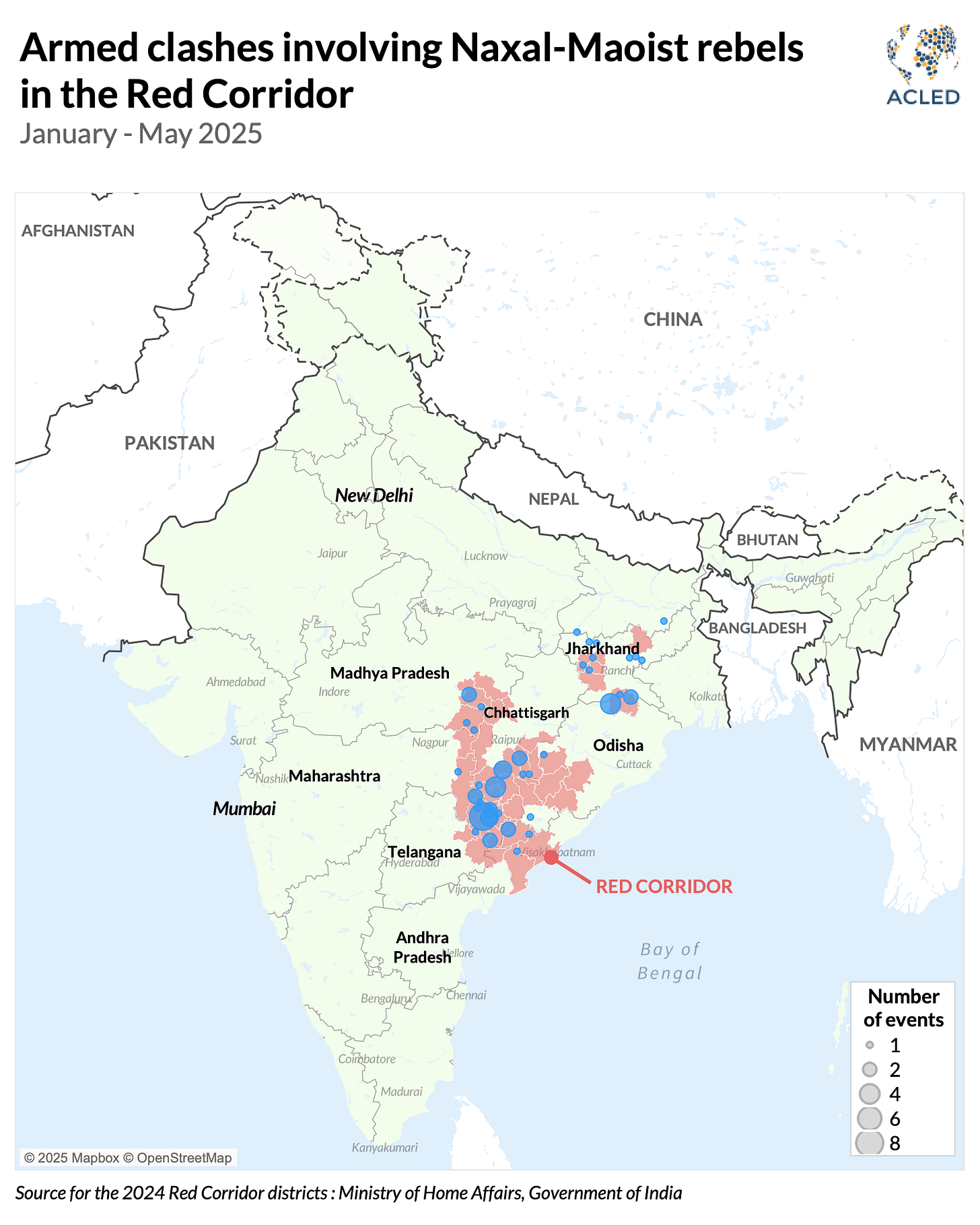

By then, the insurgency spread geographically in the shape of a “red corridor” that snaked up from three southern Indian states, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Orissa, seeping into the border districts of Maharashtra and parts of Karnataka, and traveling up into the forests of central and eastern India. Before a people’s uprising got rid of Nepal’s monarchy in 2006 and brought the Maoists into mainstream politics, that country’s insurgency was also deemed part of the “red corridor.”

Over the past two years, operations seem to have weakened, to a point of no return, the five decade-long insurgency that ran a parallel state in parts of India. According to government numbers, what’s left of its leadership after the spate of killings and surrenders is unsure and divided over the course of its “people’s war.” One turning point was the surrender of a top leader last month after he released two letters criticizing the leadership’s lack of vision and failure to adapt the insurgency to changing circumstances. The other was the killing of a commander in November.

It’s been a long and violent road. Hundreds of guerillas, police and paramilitary personnel, and ordinary people caught in the middle have been killed, public infrastructure destroyed and other excesses and rights violations committed by both sides. After reversals in which security forces lost men and resources and political leaders were soft targets, from the mid-2000s the government adopted what Prime Minister Singh described as a “two-pronged strategy” – sustained security operations against the armed insurgents and a special focus on filling the development and governance vacuum in the affected areas.

As the government poured money into a crackdown and beefed up security forces, it also made an important socio-economic intervention. The Forest Rights Act, passed in 2006, recognized for the first time the rights of tribal communities and other forest dwellers to forest resources, on which they were dependent for livelihood, habitation and other socio-cultural needs. The Naxalite/Maoist insurgency is located in Dandakaranya, a vast 90,000 sq km region encompassing districts of four states, namely Chattisgarh, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. A little less than half of this region, 39,000 sq km, comprises Bastar, a densely forested administrative division in Chhattisgarh, where several tribal communities including the Gonds and Marias live. Over the decades, Maoists had turned these areas into impenetrable bastions. The 2006 Act was an outreach by the Indian government, which virtually acknowledged that the Indian state, including the colonial one, had long deprived these indigenous groups of their rights, and was seen as correcting a historical injustice. It also acknowledged the communities’ relationship with the forests and their traditional wisdom on forest conservation.

Predictably, huge challenges have dogged the implementation of the Act. Lobbies of wildlife conservationists on one hand and corporate interests on the other have railed against this legislation for their own reasons. The area is rich in mineral resources, and mining companies have found loopholes in the act, along with willing local collaborators among politicians and bureaucrats. Tribal groups are pitted against big companies for their rights over the land. Thousands of land claims remain pending in Telangana, Maharashtra and Odisha. State governments have activated the law partially or not at all.

Whatever good was intended by the 2006 Act was also set back by a government-sponsored militia called Salwa Judum. It was raised from among the tribals in Chhattisgarh state in 2005 for counterinsurgency operations, and resulted in horrific internecine killings and retaliation by the Maoists against those who joined or supported it. Asked to choose between Salwa Judum and the Maoists, the people preferred to go with the latter. Recruitment rose. In 2011, the Supreme Court declared the militia illegal and a violation of the right to life of the people who were recruited into it, and of those who were its targets.

In sum, these areas remain impoverished and backward in all respects. But a more focused implementation of government schemes, including compensation for those displaced by mining activities, more roads, communication and connectivity and measures for their financial inclusion, have given forest dwelling communities a glimpse into the possibilities.

With no plan by the Maoist leadership for social and economic betterment, and their emphasis on war without end, the appetite for the insurgency dwindled in their own strongholds. In a twist to the tale, the leaders of the insurgency became invested in the continuance of exploitative mining contracts in areas under their control, extorting from them to raise revenues for the insurgency. The recent successes by the security forces could not have come without intelligence from the ground, a sure indicator of people’s dissatisfaction with the insurgency that claimed to speak for them.

What now? Naxalism, despite its flawed methods and single-minded focus on armed revolution, focused the nation’s attention on India’s deep inequalities and its uneven governance. Today, India is said to be a more unequal country than it was even during the British Raj, with a few billionaires holding most of the nation’s wealth while most of the rest get by on a few thousand rupees a month. Gadchiroli, a Maoist stronghold in Maharashtra, India’s most industrialized state, is also among the poorest and most backward districts in the country.

The future of the Adivasis remains uncertain. It is not clear what plans the government has to rehabilitate cadres who have surrendered or who were arrested. If the end of the Naxalite insurgency is indeed near, the government’s next challenge would be to shift gears from the hard security crackdown and frame policies that ensure that the communities living in the areas once ruled by the Maoists do not remain marginalized and hounded as suspects forever and are able to lead a life of dignity.

Several claims made, without being backed by any sources:

>the leaders of the insurgency became invested in the continuance of exploitative mining contracts in areas under their control, extorting from them to raise revenues for the insurgency.

>The recent successes by the security forces could not have come without intelligence from the ground, a sure indicator of people’s dissatisfaction with the insurgency that claimed to speak for them.

Very well written, Nirupama!