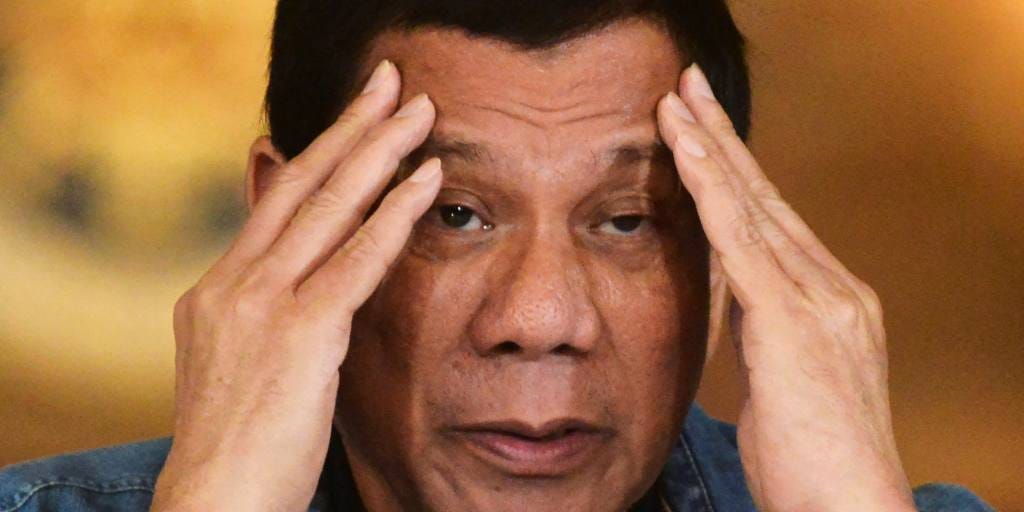

Duterte’s Teflon Starting to Fade?

Confluence of ugly events cuts into Philippine president’s aura of invincibility

The ambush and murder of four Philippine military intelligence soldiers by national police at a roadblock on the southern island of Jolo on June 30 has suddenly cast the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte in a new and unbecoming light, exacerbated by the government’s inability to get on top of the continuing fight against the Covid-19 coronavir…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.