Crisis of Paralysis in Manila

Mixed signals from the public and the president leave the Senate risking a constitutional crisis

By: Manuel L. Quezon III

What three people did following the Philippines’ May 3 midterm polls suggests that the leadership knows what’s what, and it’s this: with no clear outcome midterms, the warring President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, his terminally estranged Vice- President Sara Duterte, and the Senate President Francis Escudero are all stymied, one way or another, as they all confront unfinished business from before the elections: the impeachment trial of the vice-president.

The midterms were supposed to boost one side and diminish the other; instead, all sides are left unsure of where they stand. The result was a draw. The Marcos and Duterte coalitions elected five candidates each of a maximum of 12. What confused matters as far as both the political class and the public were concerned was the election of two more who represent the center-left forces that the Dutertes and Marcoses have tried to eliminate politically since 2016: one is a scion of the Aquinos and the other, the defeated vice-presidential standard bearer of that coalition in 2022.

The President, after announcing he was asking appointed officials, starting with his Cabinet for their “courtesy resignations,” ended up engaging in a minor reshuffle which essentially concentrated on removing the vestiges of his political accommodation with the Dutertes from his Cabinet. The Vice President, for her part, engaged in preventative rhetoric by vowing “a bloodbath” if her impeachment trial proceeds. And the Senate President picked up where he’d left off prior to the election: responding to the Philippine constitutional instruction that upon receipt of articles of impeachment, the chamber he leads is to proceed with a trial “forthwith,” by dragging his feet.

Only in the Philippines can the obvious be debated as if what has long and widely understood is suddenly newfangled and unknown. Impeachment has been in every constitution for nearly a century. Having been borrowed from the Americans, there is ample philosophical and legal precedent to address any question that might arise. The question being debated is this: can an impeachment passed by the House in the 19th Congress (which expires on June 30, 2025) be tried into the 20th Congress (which convenes on July 1, 2025), or must all the proceedings be finished before July?

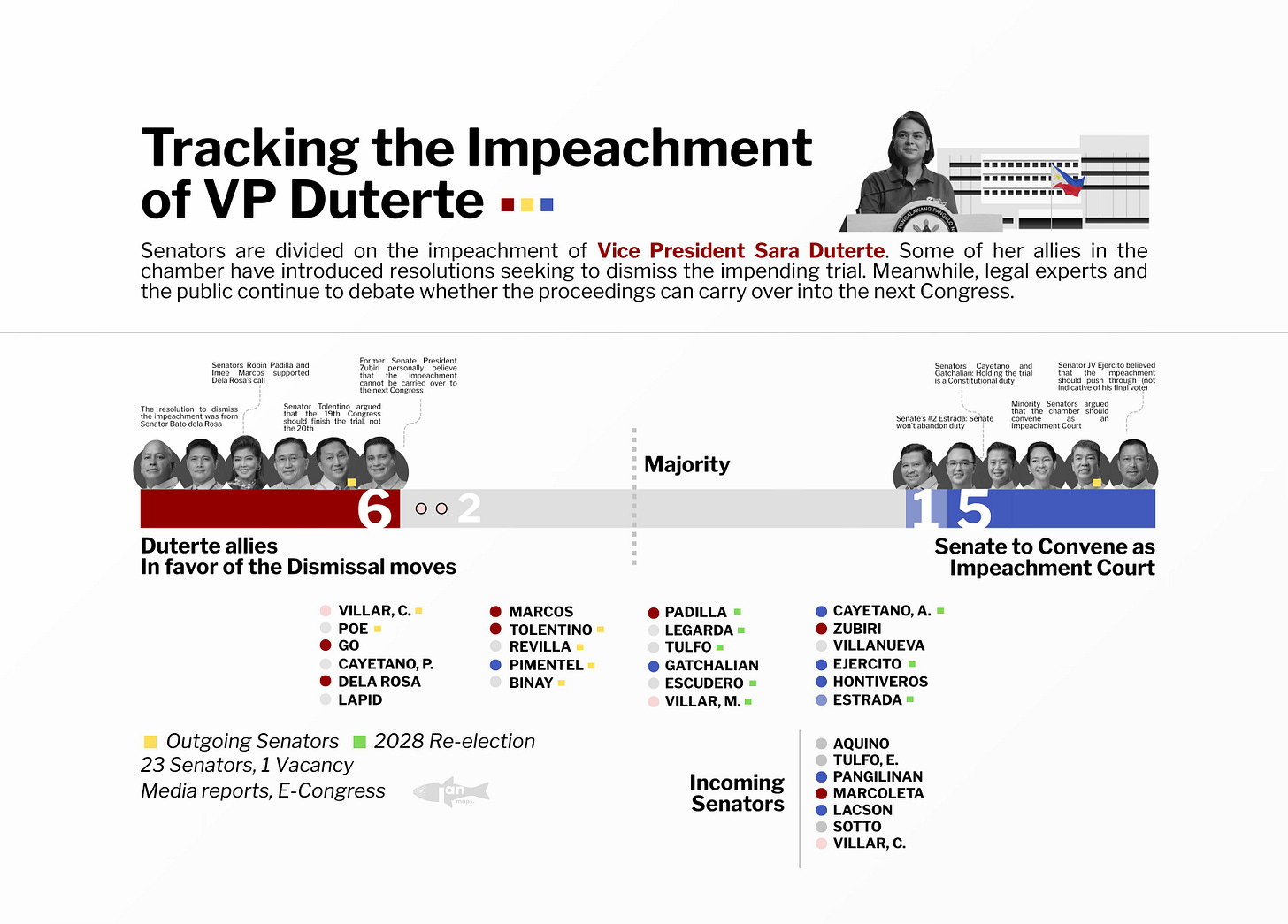

With the enthusiasm of medieval monks debating how many angels can dance on a pinhead, senators are debating—or, to be precise, speculating—on the topic even as irate civil society and educational institutions are suddenly exercising their atrophied activist muscles in outrage over the imbecility of the arguments. A resolution has been drafted by Senator Ronald dela Rosa, one of Duterte’s principal lieutenants, to dismiss the charges without bothering with a trial.

Complicating the issue is that it’s become tied to the first order of business of the incoming 20th Congress, which is the election of the officers of both chambers. The bloc identified with the Dutertes is a valuable commodity that neither of the two leading candidates—the incumbent Senate President, Francis Escudero, and a former Senate President, Vicente Sotto III, recently elected to an unprecedented fifth (nonconsecutive) term—can ignore.

Which explains the posturing of both Escudero and Sotto, who have taken to various (because ever-morphing) expressions of unease concerning the Duterte impeachment. Escudero, at the start, when the House delivered its articles of impeachment on the last session day before the election recess, had expressed the intention of mounting the trial in the 20th Congress, specifically only after President Marcos delivered his State of the Nation address in late July. He eventually had to backtrack and went through the motions of making minor preparations until he more recently said he would leave it up to the Senate as a whole to decide what to do. Sotto, for his part, says the rules are subject to interpretation, and besides, the mess is due to Escudero not getting the trial going earlier.

Here, President Marcos once more enters the scene. The election recess of Congress led to proposals that the President use his power to call Congress to a special session for the purpose of holding the impeachment trial in the midst of the campaign. It didn’t happen because the President said he’d do so if asked by the Senate and it didn’t.

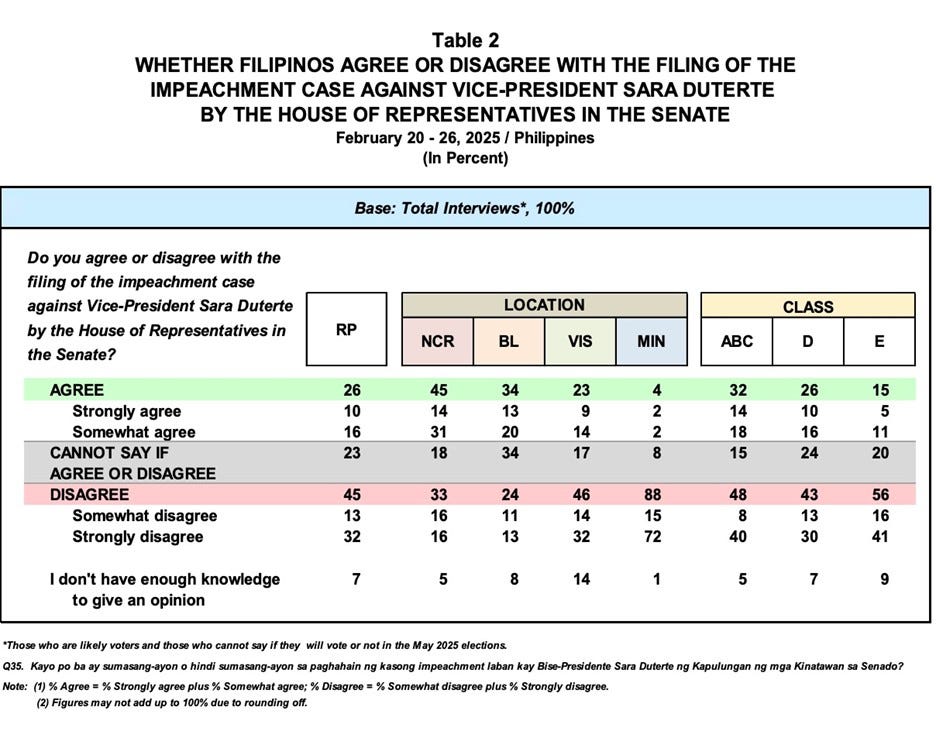

Simply put, it made no sense to mount a trial in the midst of a campaign, when the impeachment itself had become a campaign issue due to the timing of its passage by the House. The problem is that the midterm failed to resolve what it was meant to resolve: the balance of power in the Senate going into the trial, itself an outcome of public opinion as expressed in the senatorial results, concerning the two main contending parties: the Marcos and Duterte coalitions.

The Senators cannot coalesce because the verdict is unclear. In the case of tie, the burden is on the senators to sniff out for themselves, which way they think the wind is blowing in terms of divided public opinion.

Public opinion—fickle because emotional—has severely punished senators before when they misread the signs of the times in an impeachment. A whole roster of formidable veteran senators found their careers extinguished outright or handicapped for a decade because they bucked public opinion and procedurally supported embattled President Joseph Ejercito Estrada during a crucial vote on evidence during his impeachment trial. The result was a walkout by the prosecution followed by rallies in the streets preceding the withdrawal of support by the gatekeeping institutions of Philippine democracy: the church, civil society, and the military, which toppled Estrada from power.

A Philippine senator summed up political prudence in this manner: “less talk, less mistake; no talk, no mistake.” The slower the Senate creeps to a trial, the less of a chance it will fatally alienate whichever part of the electorate turns out to matter; having no trial means there is no one to alienate as a result of a verdict. The Dutertes do not want a trial at all, because evidence has a peculiar ability to foment public outrage. Senators about to leave office and those about to enter office do not want a point of no return so late, or so early, in their terms, as the case may be.

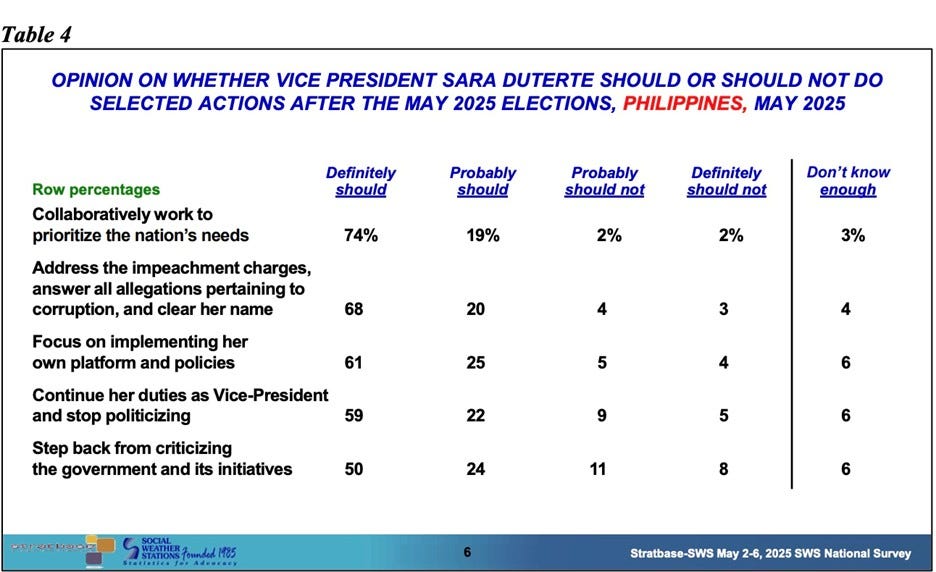

Yet again, we return to President Marcos. Time and again, he has said he didn’t want an impeachment. He has even gone so far as to publicly desire reconciliation with the Dutertes who, after all, were the ones who began hostilities. In either case, whether he is sincere or not is not the point; in a society where appearances arguably matter more than substance, it is expected of presidents to frown on any move that can cause disorder, and it is equally expected of presidents to be the first to offer an olive branch to foes. This performative aspect of the job has been satisfied and the politically-desirable answers obtained, when the Senate bogged down in intramurals on impeachment while it was Duterte who vowed a bloodbath and insultingly responded to the proffering of reconciliation –the troublemaker isn’t in the Palace.

Meanwhile, the President-as-thoroughbred knows his own political class well enough to trim down opportunities for extortion (or haggling) on the part of senators or congressmen, both of whom comprise the Commission on Appointments that must confirm or reject his new cabinet appointments. After all, the expected motions in the wake of a midterm defeat have already been made: the ritual acceptance of the popular will; offering up human sacrifices as atonement by purging the Cabinet, however lightly.

But this is not the time to expand the opportunities for horse-trading considering the conventional wisdom that an impeachment trial is one-third about the evidence (making for the strength or weakness of the case), one third-about presentation (which affects public opinion), and a third about management (however defined: often in terms of maintaining discipline or overcoming scruples).

When President Benigno S. Aquino III led the charge to impeach and convict then-Chief Justice Renato Corona, aside from the president himself taking the lead to make the case before the bar of public opinion, it was widely understood in political circles that he had two behind-the-scenes managers for the effort: Florencio Abad, who was Secretary of the Budget, and Manuel Roxas II, who was a principal lieutenant and party grandee. Marcos has taken an altogether different tack as noted above: he remains publicly above the fray. There is no sign, either, that there is anyone serving as an emissary between the Senate and the Palace: and so, to the ultimate question of just to what extent, is Marcos prepared to bet the farm, there are no signs or portents that anyone can point to.

These leave the Senate all the more isolated; it must consider bearing public opprobrium without any guarantee they will make the right bet or even receive any support, explicit or implied, from the party most aggrieved by the Dutertes –the Marcoses.

It is entirely possible that there is an impeachment manager, and that Marcos is truly keeping his cards close to his chest. It is just as possible that he has not decided if this is a battle he is willing to bet the farm on, at least not yet. He could be in the same boat as the senators: with public opinion divided, the month between the expiration of the current congress and the start of the term of the next, is a time for wheeling, dealing, and gauging public opinion by means of trial balloons –of which, as we’ve seen, there are plenty.

An impatient House of Representatives, egged on by an equally impatient civil society (enjoying the flexing of its atrophied muscles), just might relieve everyone of the burden of guessing where public opinion lies, by asking the Supreme Court to intervene by ruling on whether an impeachment trial can straddle two congresses. Senators, including those vying to be the next Senate President, can then say the Supreme Court has tied their hands.

Then the trial would proceed, but it wouldn’t just be the Vice-President in the dock: the Senate would be on trial too, since the public has expressed skepticism about its impartiality even as it expects the process to unfold and a verdict to be reached on the merits.

But even without the Supreme Court being asked to weigh in, civil society which has been feeling empowered by the controversy, is increasingly being joined by other groups previously discounted as consequential in the post-Duterte era: manifestos have been flying thick and fast as political and social groups and even the voices of some Catholic figures of influence, have embarked on organizing for a series of prayer vigils and rally to pressure the Senate to make up its mind.

This is tied to that feeling of renewed relevance and strategic importance that the formerly defeated and disillusioned center-left forces have felt in the wake of the surprise election of two of their candidates to the Senate. They simply refuse to concede the field to the Dutertes, are impatient (and generally hostile) to the Marcoses, believe in accountability, and actually have individual and collective experience with impeachments. Whether they can mobilize in numbers that can impress, and maintain the pressure so as to keep the issues front and center and thus, top of mind, is the kick-off to the month ahead that will determine the fate of impeachment.

That more senators are going on the record that institutionally, they have no choice but to proceed with an impeachment trial, suggests where public opinion stands is getting clearer to them. The longer it takes for the Duterte bloc to fail to reach a majority consensus to junk the trial, the more those still on the fence will be emboldened to take the popular path of seeing where a trial leads.

A resolution by July might then be possible, with the President having kept his powder dry by keeping everyone guessing how committed he is to any particular outcome, and without having to invite an intervention by the Supreme Court.

Manuel L. Quezon III is a Filipino writer, former television host, and grandson of former Philippine president Manuel L. Quezon