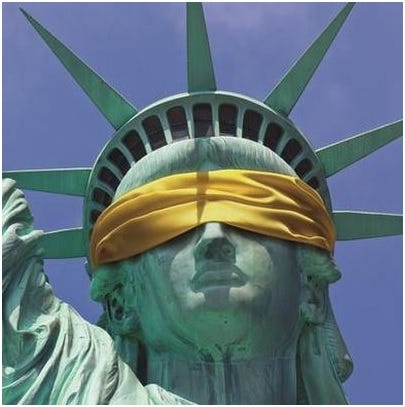

Covid-19: Excuse to Crack Down on Freedoms

Press, rights organizations under unprecedented attack

Governments in Asia and across the world are using the Coronavirus crisis to curtail civil liberties, extend surveillance to an unprecedented degree and seeking to limit freedom of the press, alarming press and civil rights protection organizations.

What follows is a partial list, given that new attacks are occurring almost every day on both individuals …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.