Chinese Cargo Vessel Sails Through Top of the World

Implications of six-day passage through northern sea route for Asia-Pacific strategic balance

By: Andy Wong Ming Jun

In September, the maritime and offshore news website gCaptain reported that the Chinese-owned and operated container ship Istanbul Bridge, made one of the fastest-recorded sailings through Arctic waters, completing the Russian Northern Sea Route in a mere six days. Having already established the viability of such a sailing route for a vessel of its size and speed as a prelude to becoming the first vessel operating a new cargo shipping route expected to not only significantly slash shipping durations between Europe and Asia but also do so with meaningfully large container shipment quantities.

Istanbul Bridge is a Panamax-sized vessel, taking its terminology from the size of the original Panama Canal locks which have been in service since the Canal’s opening to marine traffic in 1914. Panamax vessels are the baseline model size of all modern-day international container shipping since 1980, with newer vessels over the past few decades only growing ever-larger with greater cargo capacity.

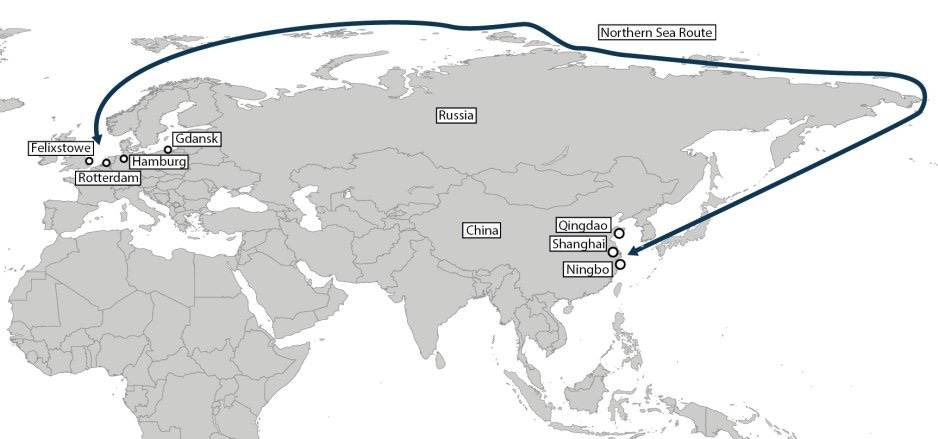

In the case of Istanbul Bridge however, the ship will not be expecting to experience the hot tropical climate of Panama anytime in the foreseeable future, but instead spend most of its time traversing the cold Russian arctic waters off the Siberian coast as the first full-time assigned vessel for the China-Europe “Arctic Express” shipping service’s inaugural sailing later this month on 20 September. The vessel’s operators, Haijie Shipping Company, expect this first voyage of its new seasonal shipping service over the icy top of the globe to take a short 18 days, linking the three major Chinese ports of Ningbo-Zhoushan, Qingdao, and Shanghai with their European counterparts at Felixstowe, Rotterdam, and Hamburg.

What makes this audacious duration forecast for this new Arctic shipping service using a route taking it through hazardous icy waters even more impressive is how a Panamax-sized vessel like Istanbul Bridge, just over three football fields long (294 meters) with a maximum cargo capacity of 4890 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) is expected to be sailing at a near-constant speed of 15 to 18 knots without requiring Russian icebreaker escort to clear a path.

Although described as “slow cruising” in industry parlance, in reality, it is not much slower than the average cruising speed of 20 to 25 knots for similar-sized vessels in open waters. Istanbul Bridge’s latest transit of the Northern Sea Route saw it hit a top speed of 18.4 knots even with cautious coastline-hugging sailing.

It is hard to overstate the significance of this new Chinese container shipping route for China’s trade links with Europe, its strategic calculus in the intensifying chess game of sea power competition with the US in the Asia-Pacific region, and the ever-deepening alliance ties between China and Russia. Should the “China-Europe Arctic Express” route prove to not only be a predictable and reliable sailing journey through the summer months but also commercially profitable and desirable by European trading partners, it could in a single stroke gift China yet another option to circumvent and render ineffective US containment strategy against itself.

The current US containment strategy against China is heavily reliant on the assumption of continued qualitative superiority and the ability to inflict significant economic turmoil by blockading Chinese trade and energy imports via the Straits of Malacca and Singapore, through which much of Chinese maritime trade currently flows.

Thanks to global warming, the Arctic is increasingly seeing more ice-free days, with the latest scientific research predicting ice-free Arctic summers by 2030 and even as soon as 2027. The steady retreat of pack ice, which usually makes much of the Arctic Ocean impassable during the colder months and navigable only by specially-built Arctic-certified icebreakers and smaller cargo vessels with thicker hulls, has opened up the much-fabled Northern passages, of which the two main routes are Russia’s Northern Sea Route and Canada’s Northwest Passage.

These routes have long been sought after in human maritime and arctic exploration efforts throughout history, as European maritime powers in the Nordics and England (later on Great Britain) sought to find a shorter route to Asia by sea sailing atop the known world in contrast to the longer land route going across the European continent and Central Asian steppes to China and India.

Having the Russian Northern Passage in the Arctic Ocean remain ice-free during the summer and possibly even autumn months annually in the near future not only makes feasible shipping voyages like that of the Istanbul Bridge on its Arctic Express route, but also presents significant upsides for consumer logistics in Europe during one of the key periods of Asia-Europe cargo shipping. For it is between June to September each year that countries in Western Hemisphere regions like Europe, the British Isles, and the North American continent see consumer retailers front-load and stockpile products scheduled for sale during the festive season leading up to Christmas between October and December.

This is usually the most profitable period in the container shipping industry, with maximum demand for cargo capacity flowing out from China as the world’s factory to Europe and North America. In the way of profit-making lies the two traditional issues goods importers have to deal with: that of unloading delay costs (demurrage) and port congestion caused by the cyclical surge of containerized cargo shipping arriving from Asia, arriving in a few major Western (in this case, European) ports within a very short time period.

Currently, Asia-Europe shipping times are in the maximal range of 45 to 60 days, given the ongoing Houthi attacks disrupting large-scale maritime passage through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, which has forced most international shipping majors to go the longer circuitous route via the Cape of Good Hope off South Africa. In this same duration, Chinese consumer goods exporters could potentially send two to three full shipments’ worth of goods to Europe via the new “Arctic Express” instead of one the long way around.

Smaller Panamax-sized container ships like Istanbul Bridge might carry much fewer containers than the modern-day behemoths capable of three to four times their container capacities, but they are much quicker and easier to unload, not to mention being able to use smaller ports and avoid congestion at larger ports.

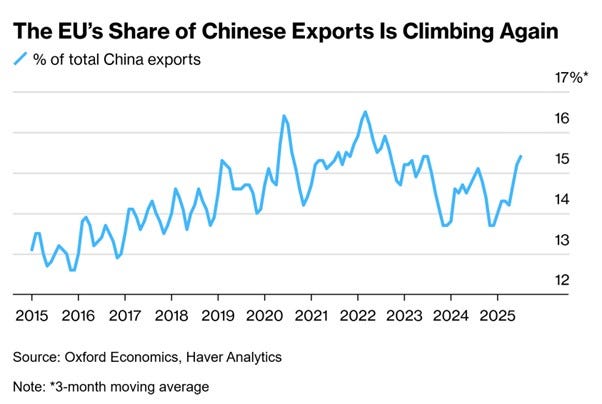

In combination, this means better container throughput for shippers and traders in Europe and China, just as China is seeing increased exports to Europe again. With global shipping logistics shifting in favour of prioritizing supply chain resilience and constant revenue inflows as opposed to fragile boom-or-bust business cycles, there might well be increased demand for “regular commuter train” cargo shipping services with shorter-distanced, more frequent sailings, creating win-win financial outcomes for European and Chinese trade.

The same benefits would be of added importance for Russia, which has seen Western economic and trade sanctions imposed for over a decade following its illegal annexation of Crimea and ongoing invasion of Ukraine since February 2022. Russia is ever more dependent on Chinese trade today to prop up its war economy finances, and whilst Russian energy exports to China are easily done overland with large throughput quantities with existing and future pipelines running through modern-day Kazahkstan, Eastern Siberia, and the Russian Far East, Russo-Sino land trade is still largely reliant on two freight train routes with average container delivery times of 21 days, compared to 18 days by sea from Southeastern Chinese ports to European ports even further than the westernmost Arctic container port Russia has at Murmansk.

Finally, if commercial cargo shipping routes like the “Arctic Express” and ships like Istanbul Bridge turn out to be harbingers of a permanent diversification of China’s maritime trade links with Europe, it would significantly strengthen China’s strategic calculus and diminish the ability of US naval strategic planning to pose a credible and crippling threat of blockading Chinese maritime trade through the imposition of the “Malacca Dilemma” via blockading the Malacca and Singapore Straits in the event of war between the two great Pacific powers.

With Russia and China ramping up joint maritime shipborne and aerial patrol operations in the Pacific High North such as an October 2024 joint coast guard patrol seeing Chinese ships enter the Arctic Ocean for the first time and a July 2024 joint bomber patrol over the Bering Sea off the coast of Alaska, it is clear that China is staking significant resources in a calculated gamble to unbalance American strategic attention which has thus far been focused on the South China Sea and Malacca Strait.

Observing civil-military fusion to the mature extent demonstrated by China’s state-owned shipbuilding industry with shipyards like Shanghai Pudong-Zhonghua capable of building some of the world’s largest container ships alongside Chinese Navy aircraft carriers, it is no stretch of the imagination that China could in future do the same and have Guangzhou Shipyard International, builder of the Polar-Class heavy deck carriers Audax and Pugnax previously featured by Asia Sentinel in June 2024, build Arctic-capable warships for China to advance its High North ambitions and pose a counter-threat against the US and its Canadian ally in the great strategic chessboard of the Asia-Pacific.

More strategic implications for the Nordic members of NATO.

The Bering Strait then becomes a bottleneck/chokepoint, with USA and Russia directly opposing each other...