By: Tim Daiss

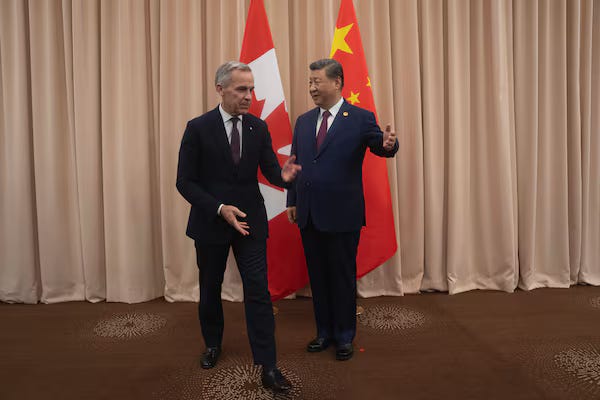

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit to Beijing last week, the first by a Canadian leader in nearly a decade, was framed publicly as a reset in Sino-Canadian trade relations. But beneath the diplomatic language and joint statements, energy quietly resurfaced as one of the most consequential subtexts of the trip. Not because Canada is about to pivot away from the US – those odds are effectively zero – but because, for the first time in years, Canada now has the physical energy export infrastructure to create a structural hedge.

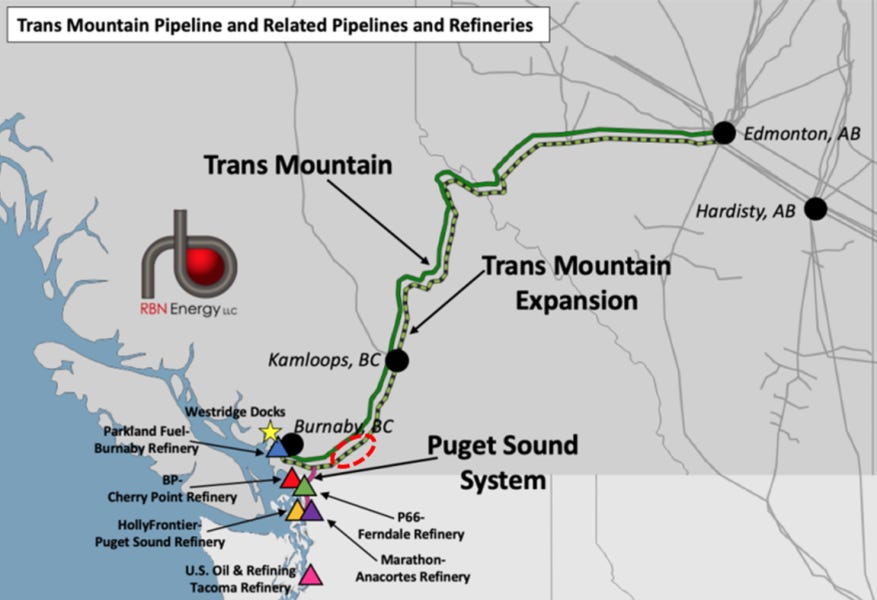

That distinction matters. For much of the past decade, discussions about Canadian oil exports to Asia were largely theoretical. Canada was structurally captive to US market demands, regardless of price signals or geopolitics. That constraint is now easing. With the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) fully operational, Canada has, for the first time since the oil sands boom, a functioning outlet to lucrative Asia-Pacific oil markets. Carney’s Beijing visit was not about dramatic realignment. It was about making optionality credible. The TMX, for its part, is a massive Canadian infrastructure project that nearly tripled the capacity of an existing pipeline to approximately 890,000 barrels per day (bpd), specifically designed to transport heavy crude from Alberta to the Pacific coast.

Infrastructure Changes the Conversation

The TMX expansion has altered Canada’s energy map in ways that go well beyond incremental export volumes. The pipeline has transformed Western Canadian crude from a landlocked resource into a Pacific-facing commodity. In recent months, record volumes have already moved through the system to the West Coast, with shipments reaching Asian buyers on a spot market basis. What TMX enables is not abandonment of exports to US Gulf Coast refineries, but leverage. For years, Canadian producers accepted structural discounts because they had no alternative buyers. That dynamic weakens when barrels can reach tidewater and, by extension, Asia.

In that sense, Carney’s visit was less about immediate cargo deals and more about signaling permanence – turning opportunistic spot trades into a durable option set. The nature of the crude itself adds weight to the argument. Canada’s oil sands produce heavy, sour crude, precisely the grade that complex refineries in Asia are designed to process efficiently. While US shale exports to Asia have surged in recent years, much of that supply is light and sweet, a grade that competes in a crowded global market often dominated by price wars.

Heavy barrels are different. Venezuelan and Russian supplies, historically important sources for Asian refiners, remain politically volatile and operationally constrained. Even when cargoes flow, they often do so through opaque channels that add risk and cost. Canadian crude, by contrast, offers reliability, contractual transparency, and a stable regulatory environment. This doesn’t mean Canadian oil will suddenly displace Middle Eastern supply or replace sanctioned barrels overnight. But it does mean Canada can credibly position itself as a supplemental source for refiners seeking diversification, especially as refinery configurations and blending economics grow more sensitive.

The Carney Factor

Carney’s personal profile also matters. Few Western leaders can speak credibly about oil, finance, and climate in the same sentence without losing one audience or the other. As a former central banker and a prominent voice in global climate finance, Carney is uniquely positioned to frame hydrocarbons not as ideological baggage but as a transitional reality. That framing was evident in how energy reportedly entered the discussions with Chinese President Xi Jinping, not as a blunt export pitch, but as part of a broader conversation about emissions management, carbon intensity, and long-term supply security. Canadian officials have increasingly emphasized carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) as a way to differentiate oil sands crude from higher-emissions alternatives. Whether that narrative convinces Chinese state-owned enterprises is an open question, but it provides political cover for engagement, particularly at a time when ESG language has become embedded, even if unevenly applied, across global capital markets.

Some observers framed the Carney visit as a geopolitical signal aimed southward. That interpretation misses the point. Canada is not choosing China over the US, nor is it signaling a break from the North American energy integration. What it’s doing is reducing vulnerability. Notably, energy markets reward optionality. When producers have only one buyer, pricing power erodes. When they have two, or even a credible second option, negotiating dynamics change. In that sense, the “hedge” is structural, not rhetorical. It exists regardless of who occupies the White House or how trade rhetoric fluctuates. This matters particularly as energy policy in major consumer countries becomes more volatile. Border adjustment mechanisms, carbon pricing disputes, and shifting industrial policy have introduced new layers of uncertainty into long-term trade flows. Having an alternative market, even one that absorbs a minority share of exports, reduces exposure to unilateral shocks.

Implications for Asia and the US

For Asian refiners, Canadian crude is not a silver bullet. Logistics costs remain higher than Middle Eastern supply, and TMX capacity, while significant, is not limitless. But as part of a diversified sourcing strategy, Canadian barrels offer something increasingly valuable: predictability. For the US, the implications are subtler. US crude exports to Asia, averaging more than 3 million bpd, are dominated by light shale oil that often competes on price rather than specification. Canadian heavy crude doesn’t directly threaten that trade, but it does introduce competition at the margins, particularly for refiners balancing complex slates.

None of this suggests a sudden reshuffling of global oil flows. What it does suggest is that Canada is no longer forced to accept its historical role as a price-taker with no exit. TMX gives Ottawa and producers alike a negotiating chip they previously lacked. And in that regard, yes, Carney’s Beijing trip could be labeled as a pushback against the US, particularly given Donald Trump’s less-than-kind remarks and posture toward its northern neighbor.

Canadian oil exports to China won’t rewrite global energy trade. But they do reflect a quieter shift underway in how middle powers think about resilience. Infrastructure, not pure ideology, is driving the recalibration. Pipelines, not press releases, determine who has options. As such, the significance of the visit lies far less in symbolism and more in arithmetic. Canada can now move barrels west as well as south. That fact alone changes the conversation.

This nails the key distinction between optionality and pivot. TMX isnt about abandoning US markets, its about erasing the structural discount Canada faced when locked into a single buyer. The heavy/sour spec advantage for Asian refiners is underplayed in most coverage, those complex refineries were designed for Venezuelan and Russian grades that are now unreliable. Ive seen firsthand how refiners value supply security over marginal pricing, and Canadas regulatory transparancy is a huge selling point when everyones hedging geopolitical risk.

The CRUX-

"Not because Canada is about to pivot away from the US – those odds are effectively zero – but because, for the first time in years, Canada now has the physical energy export infrastructure to create a structural hedge.

That distinction matters. For much of the past decade, discussions about Canadian oil exports to Asia were largely theoretical. Canada was structurally captive to US market demands, regardless of price signals or geopolitics. That constraint is now easing. With the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) fully operational, Canada has, for the first time since the oil sands boom, a functioning outlet to lucrative Asia-Pacific oil markets. Carney’s Beijing visit was not about dramatic realignment. It was about making optionality credible."