Britain Gets a New King And a Change of Style

But discontent in the Commonwealth and some say “Not our King”

By: John Elliott

The future of the British monarchy has dominated public debate in the UK during the run-up to today’s coronation of 74-year-old King Charles III. Opinion polls indicate that popular support is waning and that the idea of dynastic succession is out of tune with the times. Demonstrations with the slogan “Not My King” have appeared at the King’s public events and there are rumblings of discontent in the Commonwealth, neither of which would have been so blatant when his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, was alive.

That is offset by the tens of thousands of people swarming this past week around Buckingham Palace and the Mall, and lining today’s ceremonial route from the palace to Westminster Abbey where Charles will be crowned sitting in the Coronation Chair that dates back to 1308. Reports suggest that tomorrow (May 7) there will be more than 3,000 street party celebrations across the country, complete with masses of red, white, and blue bunting and flags.

“If you stage a coronation and nobody comes out to cheer, that’s like a defeat . .. If the streets are overflowing and people watch it, that’s the crucial popular endorsement,” Robert Lacey, a royal biographer and consultant historian for the Netflix series The Crown told the Financial Times. “People are much fonder of King Charles III than they were of Prince Charles,” he added, reflecting the way the king has taken on the role, mixing easily with crowds but maintaining a sense of dignity and commitment.

Charles’ suitability to be the King has been in doubt for decades and, until very recently, there was speculation that he should let his son William become King instead. That is now in the past and he is accepted, even though he has said that, at the age of 20, his realization that he would be king was “something that dawns on you with the most ghastly inexorable sense.”

His predecessors were little keener. King Edward VIII, who abdicated to marry an American divorcee in the 1930s, described the kingship as “an occupation of considerable drudgery.” His brother and successor, King George VI, awoke on the morning of his coronation with “a sinking feeling.”

Opinion polls are showing declining support for the monarchy, especially among the young, though Charles’s own approval ratings have risen by five points to 55 percent (the Queen’s was 75 percent). Data on British social attitudes shows a majority of the public support the institution at just over 60 percent, but those seeing it as “very important” has dropped to a 29 percent low point, with 25 percent identifying themselves as anti-monarchy republicans.

The young are far less keen than their elders, with only 36 percent wanting to keep the monarchy, compared to 40 percent who want to have an elected head of state. Among over-65s, it’s 79 percent in favor against 15 percent. Ethnic minority Britons are evenly split with 38 percent in favor and 39 percent against.

King Charles is taking on three primary responsibilities. The coronation ceremony makes him both the sovereign of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland and the supreme governor of the Church of England. He has also inherited the role of head of the Commonwealth from his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, who fixed the succession at the organization’s biennial “Chogm” conference in London in 2018.

The future of all three roles is uncertain. The sovereignty looks the most vulnerable, but is probably safe for the foreseeable future because a change would raise questions about Britain’s unwritten constitution that could prove insurmountable in the country’s current state of social and political change. Maintaining it means that the country has stability at the top, and also avoids the horrors of giving the job to a politician.

Taken together, these factors could put off any dramatic change till the King’s son, Prince William, now 40, takes over. But the monarchy seems unlikely to survive in anything like its current form till the king’s grandson, nine-year-old Prince George, comes into play.

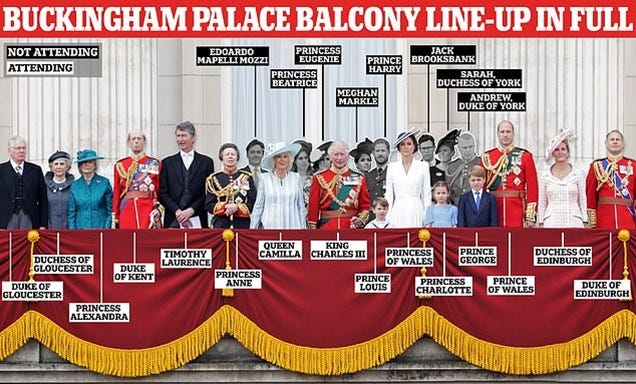

How all these pans out will depend substantially on how successfully Charles slims down the sprawling and expensive monarchy, removing the sense of dynastically inherited privilege. He is expected to allocate active roles to only about eight members of the family as “working Royals,” pushing the others into the background. Included among those absent from the active list will be his younger son, the disruptive Los Angeles-based Prince Harry, and his brother, Prince Andrew, whose private life has scandalized public opinion.

The Commonwealth's role looks the most likely to change. Prince William, the heir to the throne, has indicated that he does not expect automatically to inherit the head role and there is sufficient groundswell among the 56 member states to make it unlikely that he will do so. (There were some leaders at the 2018 Chogm who did not want Charles to take over from the Queen, but Narendra Modi, the Indian prime minister, and others pushed his case – the two men had bonded over issues such as climate change and the environment at a private dinner in Delhi a few months earlier).

The King is head of state for 14 member countries, known as Commonwealth realms, in addition to Britain. The rest of the 56 have declared themselves republics or have their own monarchies. Research for the Daily Mail has found that six of the 14 realms – Australia, Canada, the Bahamas, Jamaica, the Solomon Islands, and Antigua and Barbuda – would vote to ditch the monarchy if referendums were organized.

Losing the head of state role in the realms will be widely reported as a disaster for the monarchy, but it need not be if the somnolent and badly led Commonwealth develops into a more constructive and participative international organization. Countries such as India, which is a substantial provider of funds, would play bigger roles if the aims were clearer, and if the leadership were not centralized in the status-conscious London headquarters.

Compounding the problems, campaigners for republican and reparations movements in 12 countries have written a letter titled “apology, reparation, and repatriation of artifacts and remains.” This has been signed by representatives of Antigua and Barbuda, Aotearoa (New Zealand), Australia, the Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. “We, the undersigned, call on the British Monarch, King Charles III, on the date of his coronation being May 6, 2023, to acknowledge the horrific impacts on and legacy of genocide and colonization of the Indigenous and enslaved peoples”, says the letter.

The third responsibility, as head of the Church of England, will probably continue, though there will be criticism that Charles has this role in a country that is becoming increasingly multi-cultural. The dominating role of Christianity in the coronation service has been offset by including the heads of other churches and religions and giving them a role.

So far everything seems to have gone well, though there have been protests about heavy police security and tough new laws restricting the right to protest.

The only serious glitch has been the announcement of an invitation that will be issued during the service by the archbishop of Canterbury, who will be presiding. He will invite people watching or listening to broadcasts to join “a chorus of millions” swearing allegiance to the King in a “homage of the people”. This has never happened before and replaces a dynastic line of dukes and duchesses lining up to pledge their loyalty to the king.

The intention was no doubt good but it has been criticized. “Surely he should be pledging allegiance to us,” someone said on a television panel session two days ago.

But despite that, the coronation has energized the country into a party spirit. It has led to the arrival of thousands of tourists, and it has boosted sales for businesses. You don’t need to be a committed royalist to accept that, after the horrors of Brexit and Covid and the years of political mayhem wrought by Boris Johnson and then Liz Truss, a coronation of a member of the family that is always there is worth celebrating.

John Elliott is Asia Sentinel’s South Asia correspondent. He blogs at Riding the Elephant.