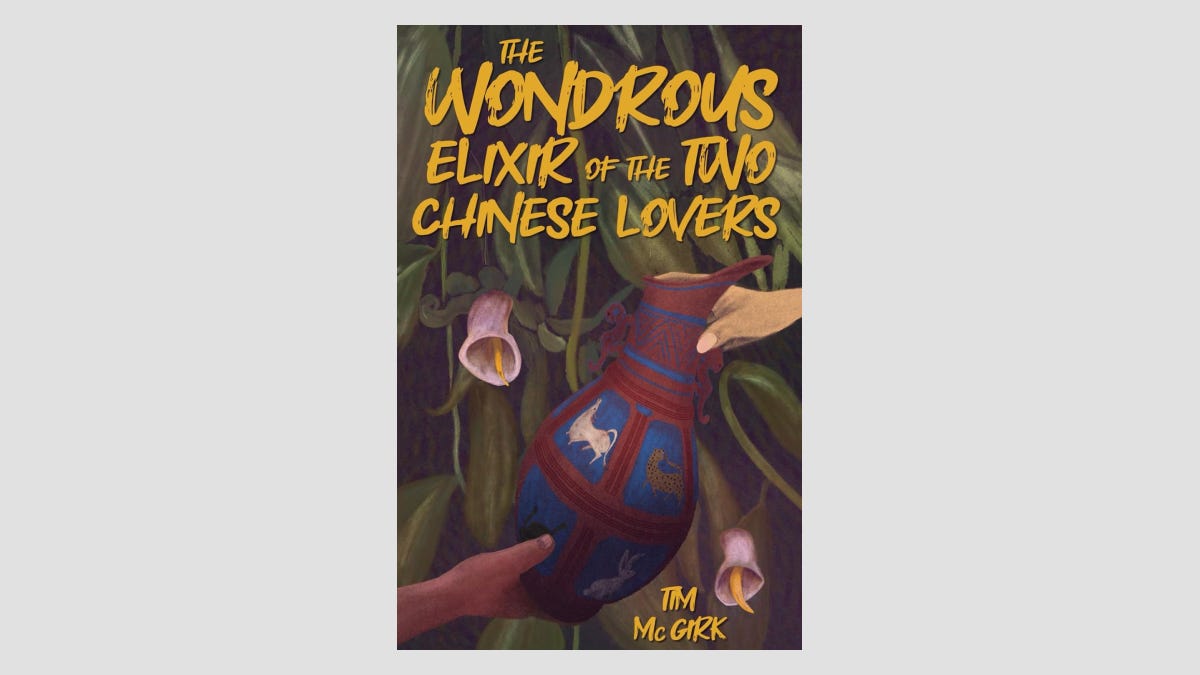

BOOK REVIEW: The Wondrous Elixir of the Two Chinese Lovers

By Tim McGirk. Plum Rain Press, Taiwan, soft cover 348 pages, US$17.95

By: Anthony Spaeth

History tells us that the first emperor of unified China, Qin Chi Huang, sent his court alchemist and sorcerer Xu Fu on two expeditions to find the elixir of immortality. We know he failed, don’t we ever, but we don’t know where Xu ended up. Legend says it was Japan.

Foreign correspondent and author Tim McGirk takes Xu’s tale much further in his novel “The Wondrous Elixir of the Two Chinese Lovers.” His protagonist Ned Sheehan, a down-at-the-heels Indiana Jones working without tenure for a third-rate university, stumbles upon Xu’s burial tomb on a Maya archeological dig in Chiapas. Included in the tomb are hundreds of clay tablets inscribed in Chinese, which when translated, provide the back story. In an adjacent tomb, Sheehan finds another corpse buried with more grandeur. It is the mother of the first Chinese emperor, and she brings the romance promised in the book’s title.

McGirk’s Xu is a guileless monk forced into adventure by an immortality-crazed emperor. He had accidentally stumbled upon a legendary chih plant, which has the effects of Viagra. That achievement lands him on a large raft dispatched to find Mt. Penglai, the home of China’s Eight Immortals, and the elixir.

The Emperor also sends his mother as punishment for a wicked past. Empress Dowager is not a title that usually quickens the pulse, but McGirk’s Zhao Ji is hot, with wrists “as delicate as willow boughs” and fetching robes concealing “her two blushing peaches of immortality.” A fearsome storm literally throws them together, and soon the 40-year-old virgin’s Jade Stalk is finding the Empress’s Red Gate in such positions as the Tiger’s Tread and Overlapping Fish Scales, which really rock the raft.

The contemporary romance is a slow-burn between Sheehan and Li Siqin, an academic researcher escaping an arranged marriage in Harbin. She flies into Chiapas to translate the clay tablets and unwittingly becomes the contact point for a group of diabolical Chinese diplomats who get around in a silver Mercedes that “glided past cantinas that exhaled drifts of sad, wounded song.” They and a separate group of Japanese hackers believe the archeological dig promises treasure beyond the material or historical: immortality itself.

McGirk warns us on page 18 that the Chinese will not be given credit for Maya architecture or any other cross-cultural pollination. His real interest is bringing together two civilizations he covered in a long career as a correspondent, and on the most fond and respectful of terms. Along with a couple of cold-blooded murders, sea monsters, and a hero of true innocence. “You are probably the only man I’ve ever lain with who doesn’t have blood on his hands,” Zhao Ji tells Xu, “whose mind isn’t elsewhere—devising plots and schemes—as he seduces me.” I love it when you talk mayhem, Empress!

According to the Records of the Grand Historian, the first great historical work of China, the real Xu Fu brought 3,000 virgin girls and boys on his final trip to hunt for the elixir. You can’t blame McGirk for reducing them to 300 colonists from good backgrounds. If one follows Chekhov’s dictum about the loaded rifle on a stage, there’s only one way to bring 3,000 virgins to a successful dramatic conclusion, and McGirk’s two Chinese lovers could never have competed—although one suspects he would have enjoyed writing it.