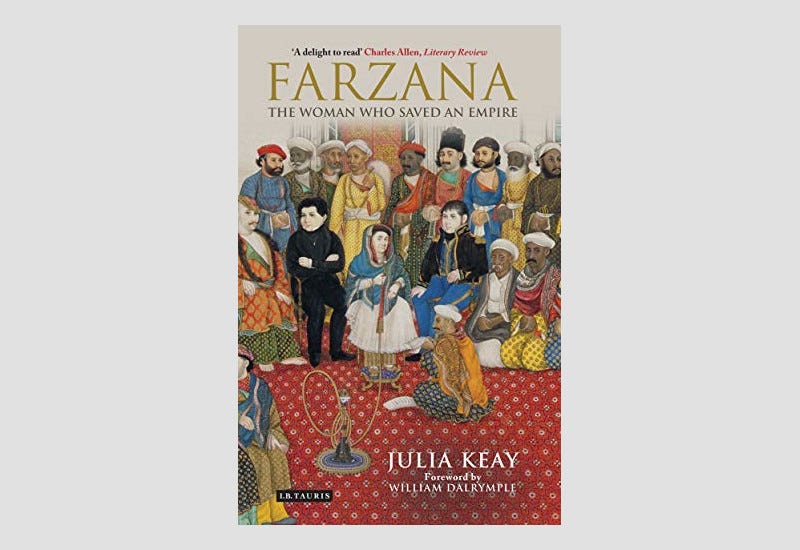

BOOK REVIEW: Farzana, The Woman Who Saved an Empire

By Julia Keay, Published by I.B. Tauris, London & New York, 2014, and HarperCollins, India, 2013, 338 pp

She is but a minor footnote in the history of India, but the amazing career of Farzana says so much about northern India in the 86 years between her birth in 1746 and death in 1836 that it is worth reading this fast-paced biography just for that.

Farzana has no known other name, according to the author -- though Zeb-un-Nissa, an honorific title, is somet…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.