BOOK REVIEW: China's Russian Princess

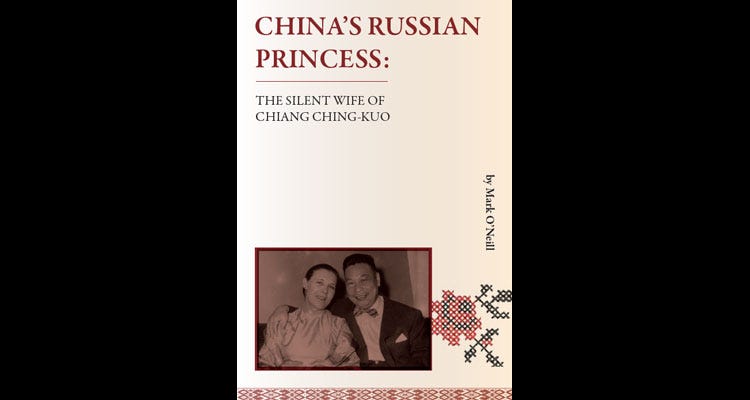

The Silent Wife of Chiang Ching-kuo, by Mark O’Neill. Joint Publishing Company, Hong Kong. Paperback, 240 pp. HK$138/ NT$620

Chiang Ching-kuo is one of the least remembered modern Asian leaders. But though he lived much of his life in the shadow of his father, Chiang Kai-shek, he deserves a better press. As president of the Republic of China on Taiwan from 1975 to 1988, he opened the road to democracy and to the government by the Taiwanese.

Even less remembered is his Russian…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.