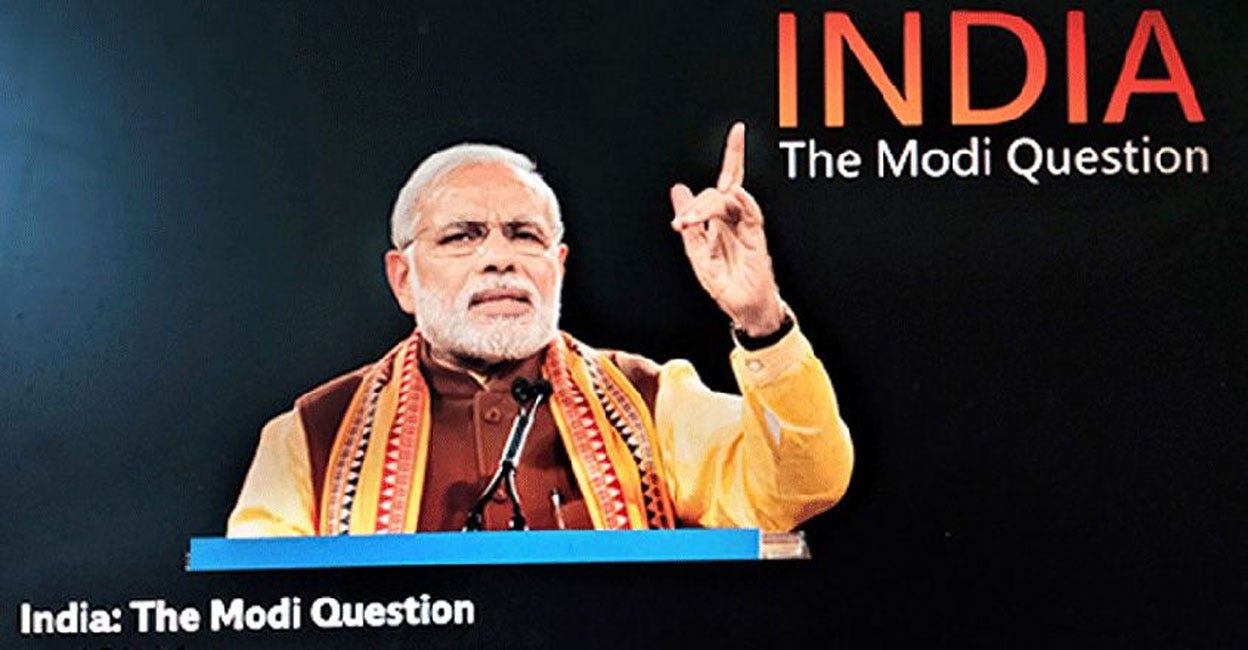

BBC’s Modi Series Leads to Crackdown on Students

“India: The Modi Question” reopens old wounds with little new detail

By: John Elliott

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. 2023 was to be the year that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi would flourish on the world stage as the head of the G20 group of nations, eclipsing criticisms of his authoritarian rule and sailing on as an international statesman to his third general election victory next year.

The election win for h…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.