Asean Summit Quandary: Dealing With Cybercrime

Festering problems in Cambodia anger South Koreans

The scheduled appearance of frustrated South Korean officials at the upcoming summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Kuala Lumpur on October 26 to push for regional cooperation against online scam operations in Cambodia is an indication of growing recognition that Asean has a huge problem as a global epicenter of cybercrime.

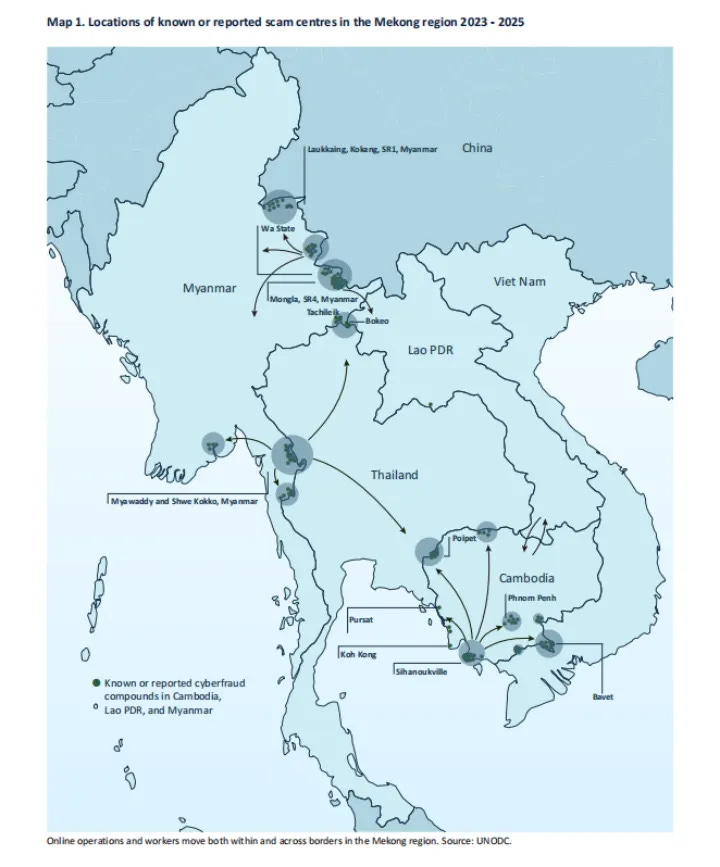

It is a social cancer not only in Cambodia but also in Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos as well, with tens of thousands of kidnapped or misled victims reportedly forced to work scamming victims worldwide and raking in billions annually.

Wi Sung-lac, the director of South Korea’s National Security Office, told a press conference last week that the Korean administration is seeking to use the Asean platform to promote a multilateral framework for combating organized crime networks operating in Cambodia and neighboring countries. “The Asean Summit will be an opportunity to establish a cooperative system, including joint investigations with policing authorities,” Wi said in a press briefing.

But given past history, it’s uncertain what reception the South Korean officials will get. Asean has a history of willfully overlooking problems. While formally committed to addressing the region’s massive drug problems, for instance, it has never effectively sought to deal with them. Its foundational principles of non-interference and consensus-based decision-making have limited its effectiveness in confronting sensitive human rights issues, refugee crises, and other social problems, allowing member states to sidestep accountability for internal problems and prevent the bloc from taking a unified, forceful stance on region-wide crises.

In 1997 –28 years ago – Asean’s Interior/Home Affairs Ministers on Transnational Crime met in Manila to discuss the drug issue. But apart from presenting an opportunity for the ministers to exchange views, there is little indication of any progress. Among interior ministers, for instance, Chou Bun Eng, Cambodia’s Secretary of State, Interior Minister – and Vice Chairperson of the National Committee for Counter Trafficking in Persons – has been described as implicated in transnational fraud.

Southeast Asian cybercrime compounds

In the case of cybercrime problems, leaders of individual governments, particularly Cambodia, have actively profited from them. Online gaming, lovelorn scams, and so-called pig butchering have been called perhaps the most dominant economic activity in the entire Mekong sub-region, equivalent to nearly half of total GDP in the primary host countries, in an explosive 73-page report by Jacob Sims, a Visiting Fellow at Harvard University’s Asia Center and an adviser to a variety of government agencies and NGOs.

South Korea is there to attest to the extent of the problems, with officials charging that hundreds of their citizens have disappeared into these online scam centers, lured to what they thought were high-paying job offers that turned into criminal bondage. So far, 330 South Koreans have been reported missing in Cambodia this year, one a 22-year-old university student later found dead, and others tortured and confined by those running the scams, South Korean officials told reporters.

As the investigative website Whale Hunting reported last week, Americans alone lost more than US$10 billion last year to online scams run out of these fortified compounds in Cambodia and other Southeast Asian nations, most of them run by Chinese mafiosi with the full cooperation of national leaders, particularly the family of Cambodian strongman Hun Sen. Top officials of the Thai government, both the previous Pheu Thai one and the current one led by Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul’s Bhumjaithai Party, have been implicated by Whale Hunting in the Cambodian network.

Asia Sentinel reported on October 16 that US authorities seized US$15 billion in bitcoin involving an online scam allegedly operated by the Cambodian conglomerate, Prince Holding Group, and its founding chairman, Vincent Chen Zhi. The case has been linked to multiple jurisdictions, including Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, where the accused allegedly established a family office, a previously notorious financial vehicle to claim tax breaks until authorities cracked down two years ago.

South Korea’s Wi noted that their intended proposal would likely center on enhancing regional coordination to address cross-border crimes linked to the Cambodian scam compounds. “Many countries are involved, and it may be efficient for the issue to be discussed at a multilateral meeting,” he said, adding that similar discussions could also take place under the United Nations and the OECD.

That’s doubtful. At least six years ago, driven by demands from Chinese leader Xi Jinping, then-Prime Minister Hun Sen implemented a ban on all online and arcade gambling across the country, including in Sihanoukville, driving out thousands of Chinese only to have the scam sites proliferate into huge compounds, as they have in Laos and Myanmar as well. Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos kicked out dozens of scam sites run by Chinese cyber-criminals last year as well, at Xi’s urging.

The criminal syndicates involved are dealing in “the top form of financial crime impacting Americans and, given the dizzying pace of growth, the harms are only projected to rise,” Sims’ report notes, enjoying explosive growth not only in Cambodia but Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines and the Marshall Islands and other areas, as Asia Sentinel has reported in multiple stories over the past two years. That has created formidable problems for banking and law enforcement officials in Hong Kong, Singapore, and other jurisdictions.

As Sim’s report emphasizes by naming the top Cambodian officials, “the crime syndicates and their opaque transnational linkages are amassing even more dangerous political power. Regional elites are implicated neck deep and, in certain contexts, the industry appears ‘too big to fail.’ The dominance and global reach of this criminal economy now pose grave security risks that go well beyond the billions of dollars lost by scam victims. The magnificent flow of laundered proceeds is flooding global markets. China’s opaque ties to the industry, as well as the mode of its law enforcement response, are subverting international norms and raising geopolitical concerns.”

Moreover, “the unprecedented centrality of the state-crime nexus in this problem-set is revealing gaps in the ability of conventional diplomatic engagement to achieve foreign policy objectives or ensure domestic security. From this vast array of risks, the industry is earning its label as “the most powerful criminal network of the modern era.”

Scamming, as the report points out, has become an enormously profitable domestic industry, likely unparalleled in the kingdom’s history, bringing in anywhere from US$12.5 billion to US$19 billion annually, “equivalent to as much as 60 percent of GDP and significantly eclipsing the country’s largest formal sector, the garment and textiles industry.”

Endemic corruption, reliable protection by the government, and co-perpetration by party elites are the primary enablers of Cambodia’s trafficking-cybercrime nexus and pose the chief barriers to combating the industry’s explosive growth, Sims writes. “Transnational fraud is one of Cambodia’s many state-abetted criminal interests—but its staggering scale and profitability have rendered this industry particularly important to the CPP’s ruling strategy,” he writes. “The most convincing explanation of that strategy from the literature…is that the CPP maintains power not thanks to popular consent to its legitimacy, but due to a highly effective and pragmatic suppression of domestic dissent.”

Phil Robertson, Director of the Asia Human Rights and Labour Advocates (#AHRLA), said actions being taken by the US and UK against cybercrime mark part of an international effort to dismantle cyber scam compounds that have spread across Cambodia.

“The US, UK, and other governments should continue expanding these efforts to target all actors in this shadowy industry, one responsible for immense suffering among victims who lose their life savings, as well as those trafficked into slavery to sustain these scams,” Robertson said.

“This enforcement action should remind the Cambodian government that they must act decisively if they want to avoid ending up on the wrong side of a global effort to shut down these scam networks once and for all,” he said.

spot on .