Al-Zawahiri’s Death: More Where He Came From

Presence in Kabul proves the Afghan Taliban’s never-ending love for jihad

By: Salman Rafi Sheikh

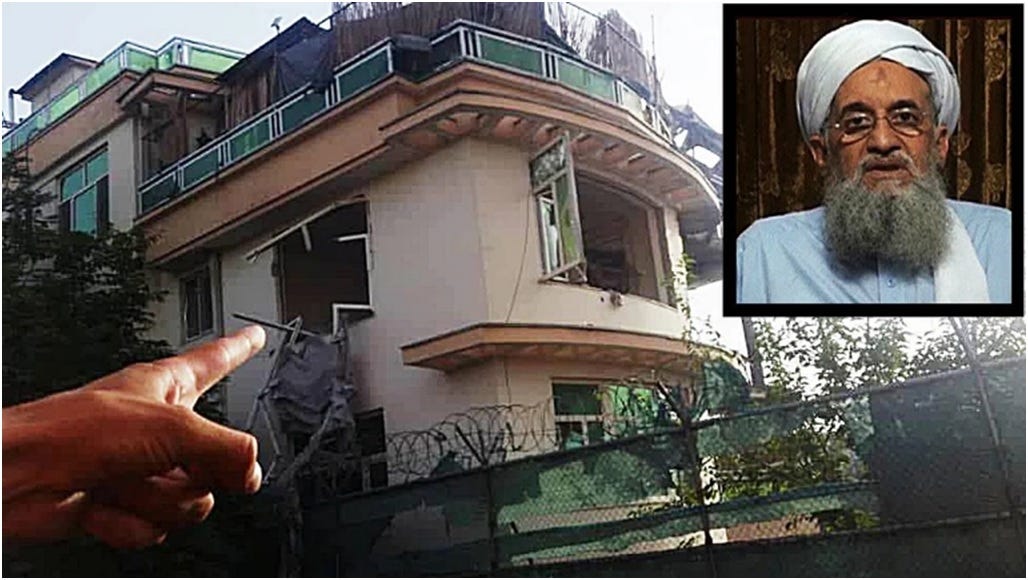

The sudden killing of al-Qaeda chief Ayman al-Zawahiri might be a moment of satisfaction for the US ‘war on terror’. But the drone strike that killed him in Afghanistan’s capital has raised more questions than answers with regards to the possibility of the end of the war.

For instance, the fact that he was living in Kabul under the …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Asia Sentinel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.