Afghanistan’s Reverse Exodus Tragedy

Iran, Pakistan force hundreds of thousands back over border

By: Amirreza Etasi

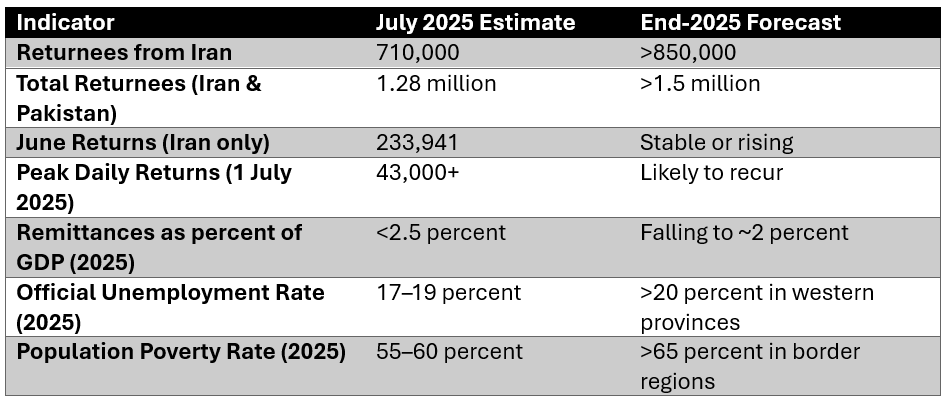

The summer of 2025 has pushed Afghanistan into the epicenter of one of the most abrupt demographic upheavals in its modern history. In fewer than six months, more than 1.2 million Afghans have been forced back from Iran and Pakistan—countries that have long served as economic lifelines and social safety valves for Afghanistan’s battered population.

Iran alone has expelled at least 710,000, with that figure likely to surge past 850,000 before the year’s end. Pakistan’s parallel deportations have only intensified the crisis. In sheer scale and velocity, this is not merely a human drama—it is a macroeconomic earthquake reverberating through every layer of Afghan society.

The Economic Undercurrents: From Labor Glut to Shrinking Remittances

Official data and field reports confirm the scope of the shock. Daily returnee peaks have exceeded 43,000, while the monthly tally has topped 230,000. With the end of 2025 looming, returns could eclipse 1.5 million—a population surge equivalent to the size of Herat or Kandahar added virtually overnight.

The consequences for Afghanistan’s fragile labor market are severe. Hundreds of thousands of returnees, overwhelmingly of working age, are pouring into a job market already beset by structural unemployment, limited formal-sector opportunities, and persistent underemployment. In provinces like Herat, Farah, and Nimroz—already burdened with chronic poverty and joblessness—real wages have plummeted. The informal economy, from construction to transportation, is saturated. Small businesses are shuttering as consumer demand dries up, and social tensions are rising as competition intensifies for every daily wage and meal.

Remittance Collapse: Vanishing Lifeline

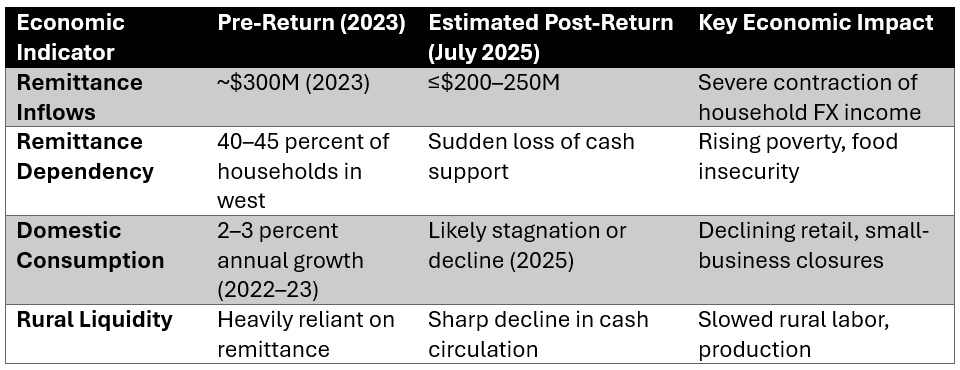

The loss is not just in jobs. For years, remittances from Afghan migrants in Iran, Pakistan, and the Gulf have been the invisible lifeblood of Afghanistan’s domestic economy. In 2023, these flows totaled only about US$300 million—a far cry from the multi-billion-dollar levels of a decade ago—with Iran accounting for a significant share. Now, as migrants are forced home, this revenue stream is drying up further.

The remittance share of GDP—once a robust 4 percent—has plunged below 2 percent, with World Bank and Migration Data Portal data suggesting it may fall to as low as 1.5 percent in 2025. In some western provinces, nearly half of households once depended on money sent from abroad. Their loss translates directly into rising poverty, acute food insecurity, and the collapse of rural liquidity.

Country at Breaking Point: Public Services Under Siege

The compressed timeline of mass returns has pushed Afghanistan’s public services—already battered by decades of war, aid dependency, and underinvestment—close to collapse. Informal settlements are mushrooming on the outskirts of border cities, with thousands housed in makeshift shelters or repurposed public buildings. Health clinics, already threadbare, are overwhelmed by waves of new patients.

Outbreaks of communicable diseases and malnutrition among children are surging. Schools face a critical shortage of teachers and classroom space, and humanitarian aid distribution is plagued by bottlenecks and chronic underfunding. According to the IOM, less than 10 percent of returnees’ basic needs are being met by either state or international agencies, with the gap widening every week.

Taliban’s Governance Stress Test

For the Islamic Emirate, this is a test of statecraft on an unprecedented scale. The Taliban lack the institutional memory, technical capacity, and resources to absorb over a million returnees into the workforce, provide housing, or maintain even minimal social protections. While there are limited attempts at short-term solutions, such as negotiating labor export agreements with Gulf states and identifying skilled returnees who could contribute to local infrastructure, these measures are insufficient against the magnitude of the challenge.

The absence of a comprehensive, data-driven reintegration strategy leaves the door open for renewed cycles of migration and the risk of social unrest, especially in already marginalized regions. Without coordinated international support, the Afghan state faces the prospect of managing a demographic crisis with little more than hope and improvisation.

Geopolitics of Forced Migration

Afghanistan’s reverse exodus is more than an acute humanitarian emergency. It is a crucible that will define the country’s economic and political trajectory for years to come. This crisis exposes deep fissures in Afghanistan’s post-occupation state-building project: the fragility of its labor markets, the perilous dependence on remittances, the chronic weaknesses in social protection, and the limits of Taliban governance.

How and whether Afghanistan’s rulers, with the support of the international community, can turn a wave of human displacement into a foundation for long-term stability and growth remains an open question. What is clear is that the outcome will reverberate far beyond Afghanistan’s borders, shaping migration patterns, security risks, and development prospects across the region.

Amirreza Etasi has served in management roles in Iran’s oil and gas sector, while contributing in-depth analysis to Donya-e-Eqtesad, Jahan-e-Eqtesad, Bourse News, and Shargh. He can be reached at Amir.etasi@gmail.com.

A very important piece. The scale of forced returns is shocking, and the humanitarian impact is deeply worrying.

The people of Afghanistan have collectively made some very choices over the past 50 years and they must live with the consequences. The people of Europe, North America and Australia should also expel the Afghans, Pakistanis and other undesirables. Let them learn and adapt or perish.